Is encryption a human right? Voices of human rights actors

1 Dec 2022 07:45h - 09:15h

Event report

Encryption enables security in the online environment where different blurred lines affect how and how much information is shared. Encryption gives the option of secure online communications where data is stored, accessed, shared, and even disclosed in non-transparent ways. It allows people to express unpopular opinions freely and have confidential conversations with family and friends, share confidential business information, and know their privacy is protected. When encrypted possibilities are not available, everyone is affected. But human rights defenders and vulnerable communities who are often targeted for what they see, to whom they speak, and what they say are disproportionately impacted. Encryption has a connection to physical safety as well. For example, online communications or location data that are not secure are used to track down individuals and persecute them. Awareness that the need for end-to-end encryption is not limited to messaging but extends to email, cloud sharing and data transfers must be increased.

There are many commonalities in the justifications and underlying policies that threaten encryption across regions, whether in Asia-Pacific, Latin America, and the EU. For example, the traceability mandate in Brazil, India, and Bangladesh and efforts to undermine encryption to allow law enforcement access to communications for various purported goals, including scams, keeping people safe online, etc., have similar characteristics. Three broad ways in which the government is trying to gain access to encrypted content:

- Exceptional access: telling service providers to provide targeted information.

- Client-side scanning: asking services and platforms offering encryption to scan platforms for different types of content like child sexual abuse material, unlawful content etc.

- Traceability: Asking service providers and platforms to design and share ways to discover the originator of specific information, messages, or data on their platforms (back doors). Back doors enabling exceptional access built into the platform for the government, at some point, could also become available to third parties (malicious agents) who can exploit these vulnerabilities. In western countries, legislation avoids prescriptive traceability requirements and insists that companies figure this out themselves. Governments are not only looking for specific content but a backdoor permitting for metadata and traceability. It is no longer about decrypting just one piece of content.

On encryption being an emerging first-generation right: The panellists agreed that the need is not for the right for encryption per se but for the broader rights it facilitates. Encryption is a critical enabler of many human rights like the rights to privacy, freedom of expression, and others. However, there is a need to focus on the existing rights framework rather than a tech-focused conceptualisation of these rights because technology is constantly evolving. In time we may have stronger methods of ensuring online security and safety. Today the best option is end-to-end encryption. The right to use encryption sets us up to need to fight for the right to access future tech the moment we have a stronger replacement for encryption. So the fight for encryption should focus on enabling the exercise of other human rights in the civil, social, and political arenas. For example, WhatsApp was used to mobilise mass protestors in Zimbabwe in 2016 as it was end-to-end encrypted. This kind of access to communications must not be subverted.

On framing encryption as a threat and obstacle to ensuring national security or child rights: We must break away from this polarisation between privacy and safety. Giving up privacy online cannot be seen as preserving online safety, which is why such proposals are misplaced. Privacy versus security is a false binary, and research proves that the two are mutually reinforcing and one cannot meaningfully exist without the other. If a platform introduces the slightest possibility of circumventing encryption, it loses its security and privacy. The focus should be on alternative means of identifying miscreants, preventing crime, and keeping people safe online in ways that don’t jeopardise fundamental human rights.

Moreover, legislation should be drafted so that it is immune from misuse by design. Currently, citizens have to count on their governments’ good (or bad) intentions. Only principle-based-by-design solutions can prevent the arbitrary application of encroachment on encryption and other protective technologies.

By Kaarika Das

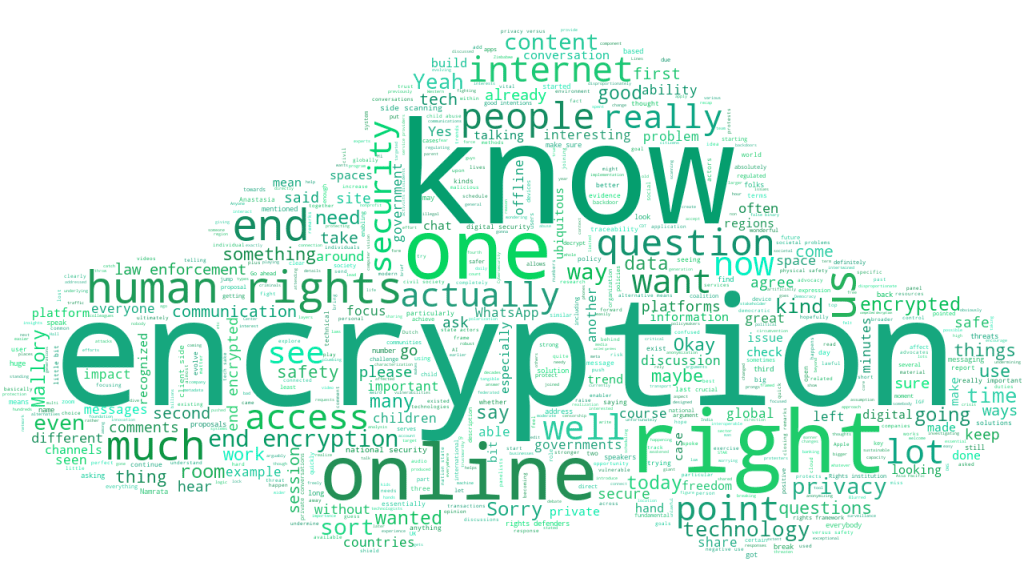

The session in keywords

Related topics

Related event