Key takeaways from the sixth UN session on cybercrime treaty negotiations

The 6th Session of the Ad Hoc Committee on Cybercrime finished its work, and one final round of inter-state negotiations is left. Is there a treaty text yet, and are states close to a final agreement?

The 6th session of the Ad Hoc Committee (AHC) to elaborate a UN cybercrime convention is over: From 21 August until 1 September 2023, in New York, delegates from all states finished another round of text-based negotiations. This was a pre-final session before the final negotiation round in February 2024.

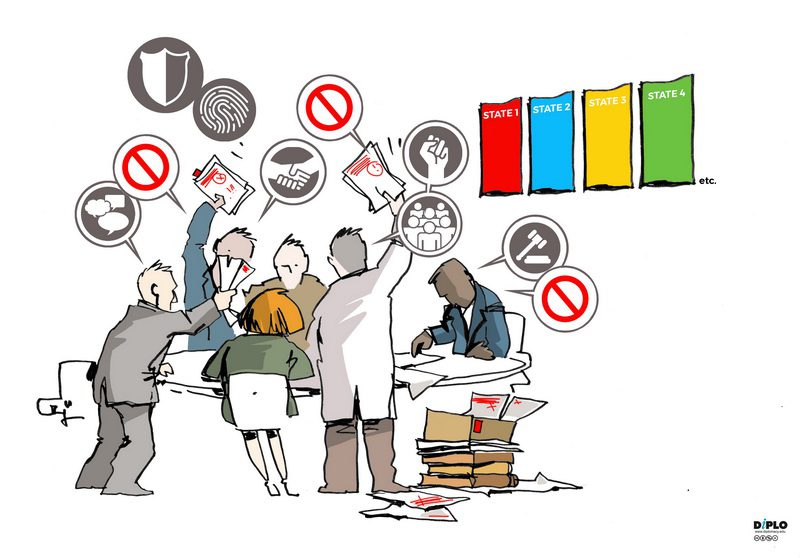

Stalled negotiations over a scope and terminology

Well, reaching a final agreement does not seem to be easy. A number of Western advocacy groups and Microsoft publicly expressed their discontent with the current draft (updated on 1 September 2023), which, they stated, could be ‘disastrous for human rights’. At the same time some countries (e.g. Russia and China) shared concerns that the current draft does not meet the scope that was established by the mandate of the committee. In particular, these delegations and their like-minded colleagues believe that the current approach in the chair’s draft does not adequately address the evolving landscape of information and communication technologies (ICTs). For instance, Russia shared its complaint about the secretariat’s alleged disregard for a proposed article addressing the criminalisation of the use of ICTs for extremist and terrorist purposes. Russia, together with a group of states (e.g. China, Namibia, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia and some others), also supported the inclusion of digital assets under Article 16 regarding the laundering of proceeds of crimes. The UK, Tanzania, and Australia opposed the inclusion of digital assets because it does not fall within the scope of the convention. Concerning other articles, Canada, the USA, the EU and its member states, and some other countries also wished to keep the scope more narrow, and opposed proposals, in particular, for articles on international cooperation (i.e. 37, 38, and 39) that would significantly expand the scope of the treaty.

The use of specific words in each provision, considering the power behind them, is yet another issue that remains uncertain. Even though the chair emphasised that the dedicated terminology group continues working to resolve the issues over terms and propose some ideas, many delegations have split into at least two opposing camps: whether to use ‘cybercrime’ or ‘the use of ICTs for malicious purposes’, to keep the verb ‘combat’ or replace it with more precise verbs such as ‘suppress’, or whether to use ‘child pornography’ or ‘online child sexual abuse’, ‘digital’ or ‘electronic’ information, and so on.

For instance, in the review of Articles 6–10 on criminalisation, which cover essential cybercrime offences such as illegal access, illegal interception, data interference, systems interference, and the misuse of devices, several debates revolved around the terms ‘without right’ vs ‘unlawful’, and ‘dishonest intent’ vs ‘criminal intent’.

Another disagreement arose over the terms: ‘restitution’ or ‘compensation’ in Article 52. This provision requires states to retain the proceeds of crimes, to be disbursed to requesting states to compensate victims. India, however, supported by China, Russia, Syria, Egypt, and Iran proposed that the term ‘compensation’ be replaced with ‘restitution’ to avoid further financial burden for states. Additionally, India suggested that ‘compensation’ shall be at the discretion of national laws and not under the convention. Australia and Canada suggested retaining the word ‘compensation’ because it would ensure that the proceeds of the crime delivered to requesting states are only used for the compensation of victims.

The bottom line is that terminology and scope, two of the most critical elements of the convention, remain unresolved, needing attention at the session in February 2024. However, if states have not been able to agree for the past 6 sessions, the international community needs a true diplomatic miracle to occur in the current geopolitical climate. At the same time, the chair confirmed that she has no intention of extending her role beyond February.

Hurdles to deal with human rights and data protection-related provisions

We wrote before that states are divided when discussing human rights perspectives and safeguards: While one group is pushing for a stronger text to protect human rights and fundamental freedoms within the convention, another group disagrees, arguing that the AHC is not mandated to negotiate another human rights convention, but an international treaty to facilitate law enforcement cooperation in combating cybercrime.

In the context of text-based negotiations, this has meant that some states suggested deleting Article 5 on human rights and merging it with Article 24 to remove the gender perspective-related paragraphs because of the concerns over the definition of the ‘gender perspective’ and challenges to translate the phrase into other languages. Another clash happened during discussions about whether the provisions should allow the real-time collection of traffic data and interception of content data (Articles 29 and 30, respectively). While Singapore, Switzerland, Malaysia, and Vietnam proposed removing such powers from the text, other delegations (e.g. Brazil, South Africa, the USA, Russia, Argentina and others) favoured keeping them. The EU stressed that such measures represent a high level of intrusion and significantly interfere with the human rights and freedoms of individuals. However, the EU expressed its openness to consider keeping such provisions, provided that the conditions and safeguards outlined in Articles 24, 36 and 40(21) remain in the text.

With regard to data protection in Article 36, CARICOM proposed an amendment allowing states to impose appropriate conditions in compliance with their applicable laws to facilitate personal data transfers. The EU and its member states, New Zealand, Albania, the USA, the UK, China, Norway, Colombia, Ecuador, Pakistan, Switzerland, and some other delegations supported this proposal. India did not, while some other delegations (e.g. Russia, Malaysia, Argentina, Türkiye, Iran, Namibia and others) preferred retaining the original text.

Articles on international cooperation or international competition?

Negotiations on the international cooperation chapter have not been smooth either. During the discussions on mutual assistance, Russia, in particular, pointed out a lack of grounds for requests and suggested adding a request for “data identifying the person who is the subject of a crime report” with, where possible “their location and nationality or account as well as items concerned”. Australia, the USA, and Canada did not support this amendment.

Regarding the expedited preservation of stored computer data/digital information in Article 42, Russia also emphasised the need to distinguish between the location of a service provider or any other data custodian, as defined in the text, and the necessity to specifically highlight the locations where data flows and processing activities, such as storage and transmission, occur due to technologies like cloud computing. To address this ‘loss of location’ issue, Russia suggested referring to the second protocol of the Budapest Convention. The reasoning for this inclusion was to incorporate the concept of data as being in the possession or under the control of a service provider or established through data processing activities operating from within the borders of another state party. The EU and its member states, the USA, Australia, Malaysia, South Africa, Nigeria, Canada, and others were among delegations who preferred to retain the original draft text.

A number of delegations (e.g. Pakistan, Iran, China, Mauritania) also proposed an additional article on ‘cooperation between national authorities and service providers’ to oblige the reporting of criminal incidents to relevant law enforcement authorities, providing support to such authorities by sharing expertise, training, and knowledge, ensuring the implementation of protective measures and due diligence protocols, ensuring adequate training for their workforce, promptly preserving electronic evidence, ensuring the confidentiality of requests received from such authorities, and taking measures to render offensive and harmful content inaccessible. The USA, Georgia, Canada, Australia, the EU, and its member states, and some other delegations rejected this proposal.

SDGs in the scope of the convention?

An interesting development was the inclusion of the word ‘sustainability’ under Article 56 on the implementation of the convention. While sustainability was not mentioned in the previous sessions, Australia, China, New Zealand and Yemen, among other countries, proposed that Article 56 should read: ‘Implementation of the convention through sustainable development and technical assistance’. Costa Rica claimed that such inclusion would link the capacity building under this convention to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)”. Additionally, Paraguay proposed that Article 52(1) should ensure that the implementation of the convention through international cooperation should take into account ‘negative effects of the offences covered by this Convention on society in general and, in particular, on sustainable development, including the limited access that landlocked countries are facing’. While the USA and Tanzania acknowledged the importance of Paraguay’s proposal, they stated that they could not support this edit.

What’s next?

The committee will continue the negotiations in February 2024 for the seventh session, and if the text is adopted, states will still have to ratify it afterwards. If, however, ‘should a consensus prove not to be possible, the Bureau of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) will confirm that the decisions shall be taken by a two-thirds majority of the present voting representatives’ (from the resolution establishing the AHC). The chair must report their final decisions before the 78th session of the UN General Assembly.