Contact tracing apps

In an effort to limit the spread of COVID-19 and to start opening up their economies, many countries have started to implement contact tracing as one of the measures. Traditional contact tracing, where a public health official interviews an infected person to determine the places and people they came into contact with, is still in place. However, the traditional method requires a lot of resources and time, is heavily reliant on the recollections of the infected individual, and cannot identify people that may have been exposed to the illness in question if the infected person did not know them personally. The traditional method of contact tracing is also not scalable to the extent needed to control the COVID-19 pandemic. For this reason, many countries already use or started to develop – either themselves or in cooperation with large tech companies – cell phone applications tracing the movement and contacts of individuals (i.e. contact tracing apps).

These apps are used to identify persons who were in contact with an infected individual. Contact tracing apps store location data and/or data indicating proximity to other devices. Should the user become sick, the app is able to alert others who were closeby or in contact with the individual that they have been exposed to COVID-19 and should take precautionary measures, such as testing or quarantine. When systematically applied, contact tracing can break the chains of transmission of an infectious disease and should thus be an essential public health tool for controlling infectious disease outbreaks.

The implementation of contact tracing apps in any form raises many issues and concerns. Important considerations include the effectiveness of the contact tracing through apps (adoption rates, exclusion of certain segments of population), technological challenges (limitations of bluetooth technology), and impacts on privacy and human rights, as well as issues of interoperability of contact tracing apps launched by different countries and the role of the international organisations in this setting.

Types of contact tracing apps

There are two types of contact tracing apps: centralised and decentralised.

For a centralised contact tracing app, the data from a user’s cell phone is stored in an external database administered by the government and is to be used based on the discretion of public health authorities. The primary consideration for governments in this case is their ability to analyse data during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The main concerns with centralised apps include the ability of governments to extend surveillance or to use the data collected for purposes other than the public health emergency at hand, risks associated with cybersecurity, and the privacy of users.

Many countries have therefore implemented decentralised contact tracing apps, or have switched from centralised to decentralised apps. In the case of decentralised contact tracing apps, the data is only stored on a user’s device. The app utilises Bluetooth to detect its proximity to other devices (i.e. ‘digital handshake’). The downsides of this model are the limitations of the Bluetooth technology itself, as the proximity of nearby devices can be measured inaccurately.

The debate on choosing between centralised or decentralised tracing apps has been most prominent in the EU. The Pan-European Privacy Preserving Proximity Tracing (‘PEPP-PT’) project was comprised of more than 130 members across eight European countries, including scientists, technologists, and other experts and was considered to be the leading European initiative for the development of a contact tracing app. However, it ran into a significant controversy around project transparency and centralised database storage, after which the participants abandoned it.

Apps based on the DP3T open protocol developed by École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne and ETH Zurich, among others, store data in a decentralised fashion and are viewed as apps that can provide greater data security and are preferred by the European Parliament; such apps are already being used by countries like Austria and Ireland.

Apps developed based on Google and Apple Application Programming Interface (API) have privacy and security in mind. Inspired by DP3T, they are based on decentralised data storage and were adopted by countries such as Germany, Latvia, and Estonia.

Adoption and effectiveness of contact tracing apps

The use of the contact tracing apps and their effectiveness heavily depends on the:

- segment of population with cell phones supporting contact tracing technology,

- adoption rate by the users, and

- interoperability of different types of contact tracing.

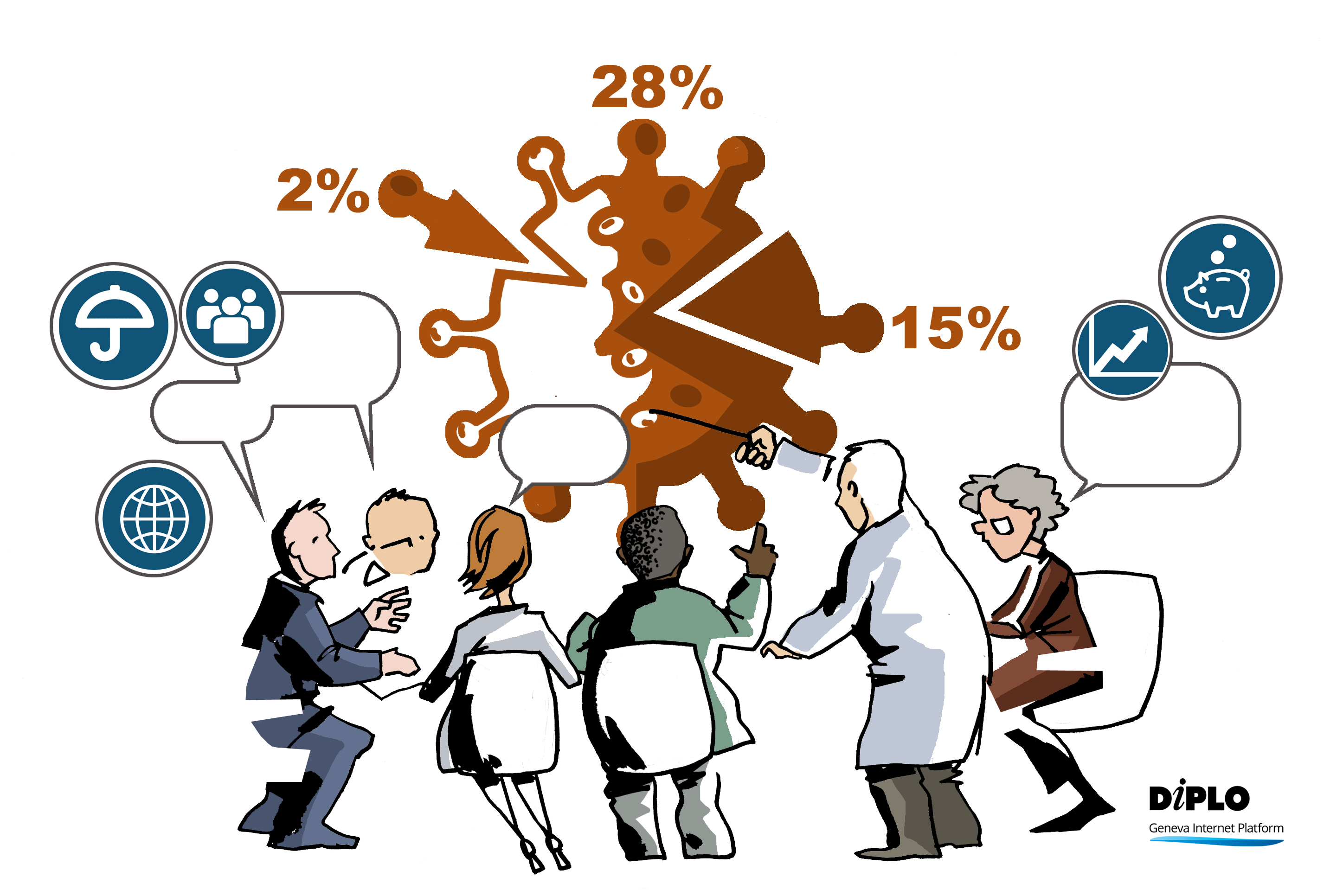

In general, about 80% of the population in developed countries has smartphones able to support contact tracing. The adoption rate of the contact tracing app in order to limit the spread of COVID-19 is approximately 60%. In India, Southeast Asia, and most of Africa, smartphone ownership is too low to reach the threshold for contact tracing to be effective.

Certain countries, like South Korea, Singapore, or Uganda, already have experience with fighting epidemics and therefore had contact tracing apps in place to limit the spread of COVID-19. The efficiency of the response in these countries has drawn the attention to contact tracing apps as an effective tool.

There are many approaches to the implementation of contact tracing apps and there are several types of such apps. Belgium and Sweden, for example, have currently forgone the use of the app relying solely on the traditional contact tracing. Others, like the UK, France, Poland, Singapore, and Thailand, are looking into launching or have already launched centralised versions of the app developed through their public health authorities. Germany, Israel, Indonesia, and Iceland on the other hand have launched decentralised apps.

According to findings by several research institutes and civil rights organisations, there is a common view that contact tracing apps cannot curb the spread of COVID-19. The technical community has voiced doubts about the accuracy of the contact tracing via decentralised apps as well. Jason Bay, the product lead for Singapore’s TraceTogether app was asked whether contact tracing apps worked and stated: ‘If you ask me whether any Bluetooth contact tracing system deployed or under development, anywhere in the world, is ready to replace manual contact tracing, I will say without qualification that the answer is, no’.

According to the Ada Lovelace Institute, there are four main points that contact tracing apps must comply with:

- Represent accurate information about infection or immunity;

- Demonstrate technical capabilities to support the required functions;

- Address various practical issues for use, including meeting legal tests; and

- Mitigate social risks and protect against exacerbating inequalities and vulnerabilities.

On the other hand, proponents of contact tracing apps argue that even if the apps are not strictly necessary to curb the spread of the virus, they do contribute in conjunction with other precautions, such as manual contact tracing, social distancing, and the limitation of gatherings and movement.

Sweden is the only developed country that has not implemented a contact tracing app due to the lack of necessity and efficiency. Sweden collects information regarding infections and traces contacts only through healthcare provider networks.

Limitations on human rights in times of public health emergencies

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, many countries resorted to implementing restrictions on the rights of their citizens in order to contain the spread of the virus and flatten the curve. Such restrictions included restrictions of free movement by imposing quarantine rules on large segments of population, closing borders and limiting travel, limiting the right of assembly by restricting large gatherings of people, and in some cases, infringing on the sanctity of one’s home by allowing for the entry of officials into homes for public health reasons. As countries return to normal and ease these restrictions, contact tracing apps come into play as a tool to help limit the spread of the virus in a potential second wave.

Any discussion involving contact tracing apps touches upon issues such as the protection of privacy, both in the cases of centralised and decentralised apps. The more types of data gathered, the longer it is gathered for, and the more parties have access to it, the greater is the intrusion into privacy. The type and amount of data collected from users varies heavily by country. The least amount of information is collected through anonymised location data via Bluetooth proximity tracing stored on users’ devices, therefore decentralised apps are considered the most privacy friendly. On the other hand, some countries, such as South Korea, Russia, or China, collect vast amounts of personalised information through centralised contact tracing apps: identifiable data about tax and personal identifications, credit card transactions, transportation and work, health conditions, facial recognition data, and GPS data, which are stored in a centralised database governed by state authority.

The data gathered by the contact tracing apps is subject to national laws and regulations, which varies widely. The implementation of contact tracing apps has highlighted the need to adopt or to amend data protection legislation.

The USA currently does not have federal legislation governing data protection, which would set standards for the whole country. The current crisis has accelerated discussion on the COVID-19 Data Protection Act, and the Exposure Notification Privacy Act in the US Senate. In the absence of federal laws, state data protection laws apply. Currently, only three US states are using contract tracing apps – all centralised – Utah, North Dakota and South Dakota. While these apps’ privacy policies regulate that they only release location data to public health officials when an individual is confirmed to be sick and that all of their data is deleted after 30 days, each of these states have breached their own privacy policies to some extent.

In South Korea the Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA) was enacted in 2011. The 2015 MERS outbreak, however, triggered amendments through the Contagious Disease Prevention and Control Act (CDPCA) that overrode certain provisions of PIPA and other privacy laws. In 2020, PIPA was amended to clarify the definition of data, its use and methods of its processing. As a result, South Korea, which has one of the most intrusive data collection practices through contact tracing app, allows for the automatic suspension of certain privacy and data protection regulations in the event of public health emergencies.

In Australia, the Privacy Amendment (Public Health Contact Information) Act 2020 (Cth) was enacted on May 15, 2020. The Act provides an addition to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) that specifically regulates the use and disclosure of data collected when people download and use the Australian government’s COVID-19 contact tracing app, COVIDSafe. It contains additional protections that provide the national privacy regulator — the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) — with oversight of the data collected by the app, thus addressing the privacy concerns.

Belgium is currently considering a draft law for the creation of a database for COVID-19 tracking. According to the draft law, Sciensano (the Belgian research institute and public health institute) would be responsible for collecting and saving the health and medical data of patients from various sources (e.g. doctors or medical/healthcare organisations) in a database along with the personal data of individuals. The Belgian Data Protection Authority voiced many concerns and criticisms regarding the draft law and has asked for its amendment.

Oversight by data protection authorities and national agencies over data collection through contact tracing apps is essential for privacy protection. More than 60 global data protection authorities and governmental agencies have issued specific guidance on health data collection, COVID-19 diagnosis disclosure, work-at-home practices, and return-to-work approaches.

Countries that have launched contact tracing apps without impact evaluations are being called out by privacy groups. This is the case in the UK, which launched a centralised contact tracing app developed by the National Health Service envisioning the retention of collected data for 20 years. Now privacy groups are preparing a legal challenge against the UK government stating that it failed to provide a legally required impact evaluation and that the proposed data processing and storage breaches users' privacy.

The impacts of contact tracing apps go beyond privacy considerations and potentially infringe on other rights. There has been backlash against certain groups who are accused of spreading the virus based on the information from contact tracing apps. For instance, an LGBTQ club in South Korea, through the use of contact tracing, has been suspected to have created a hotspot for the spread of COVID-19, which resulted in social backlash against the LGBTQ community in an already conservative and traditional society. In the USA, statistics show that COVID-19 has been hitting poorer communities harder; particularly the African-American and Hispanic communities, resulting in these groups being socially stigmatised. In the state of Michigan, 40% of COVID-19 related deaths were African-American, who only make up 14% of the state’s population.

Also, over the course of the social unrest in the USA and beyond, several human rights organisations have expressed concerns about the misuse of contact tracing apps for the surveillance of protestors, activists, and demonstrations resulting in the infringement of rights such as the right of association, right to unionise, and the freedom of speech and expression.

Additional global concerns are related to the segments of population that do not have access to Internet and/or are not digitally literate, women, as well as vulnerable groups such as disabled persons, older persons, refugees, and displaced persons. These segments of the population are disproportionately affected by the lack of access and are also in a higher risk category for the COVID-19.

The question of how the data is used and how long it should be stored is on national regulatory agendas as well. The concern here is the possibility of surveillance by the state, particularly should data use and storage not be limited. While most countries have mandated that data be deleted after a certain amount of time (i.e. a number of weeks or after the pandemic is over), some countries do not have such regulations. As previously noted, the UK intends to keep collected data for 20 years and use it for analysis that could contribute to the prevention of other health crises. China, where the contact tracing app collects a wide variety of personal information and is required to access buildings and public transportation, has also implied that it does not intend to stop collecting data when the COVID-19 pandemic is over.

Cross-border aspects and interoperability

While the pandemic is global, solutions for contact tracing are fragmented and local, making the interoperability of apps one of the main challenges for the effectiveness of this approach. As national borders open and travel increases, the question of interoperability between contact tracing apps comes into play, particularly when it comes to cross-border workers, tourism, and business trips.

Within the EU, the European Commission’s eHealth Network published its interoperability guidelines for approved contact tracing apps, guiding developers when designing and implementing applications and back-end solutions to ensure the efficient tracing of cross-border infection chains. The new interoperability guidelines were agreed upon by the EU member states with the support of the European Commission. They lay down common and general principles with the aim of ‘ensuring that tracing apps can communicate with each other when required, so citizens can report a positive test or receive an alert, wherever they are in the EU and whatever app they are using’. The guidelines also include technological parameters to ensure swift implementation by developers working with national health authorities.

In order to achieve technical interoperability, EU member state back-end servers must seamlessly communicate between themselves using a trusted and secure mechanism. All approved apps must be linked to these back-end servers so that when roaming users upload information regarding their proximity encounters, it is also uploaded to the home country back end. Additionally, these apps will need to have a common approach to detecting proximity between devices, and they should allow roaming individuals to be alerted with the relevant information in a language they understand.

Looking at interoperability from the global perspective, it clearly comes with big challenges - not only due to different architectures and back-end servers, but also due to likely increased privacy concerns, differing data localisation regulations, possibility of global surveillance without warrant, and issues related to the lack of legal interoperability and enforcement.

Cybersecurity concerns

Contact tracing apps, like any technology, are subject to cybersecurity concerns.

On the state level, the large amounts of data collected through centralised apps on a server are likely to attract cyber-attacks. Looking at contact tracing apps from the point of view of the users’ cybersecurity, there are several concerns that have been voiced by the privacy groups.

India’s Health Bridge app (Aarogya Setu), for example, is designed to let users check if there are infected people nearby. However, the app allows users to deceive the app by faking their GPS location in order to learn how many people reported themselves as infected within any 500-meter radius. ‘The developers of this app didn’t think that someone malicious would be able to intercept its requests and modify them to get information on a specific area’, said a French researcher known in part for finding security vulnerabilities in the Indian national ID system known as Aadhaar. ‘With triangulation, you can very closely see who is sick and who is not sick. They honestly didn’t consider this use of the app’.

In relation to the Google and Apple API app, the American Civil Liberties Union and about 200 scientists, among others, warned of the potential to overreach, and called for developers to ensure proper technical measures are taken to ensure the app is secure.

Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) has now raised similar concerns, focusing on cybersecurity risks. Specifically, the nonprofit advocacy group is worried that hackers can target the data sent from the app and undermine the system. ‘Any proximity tracking system that checks a public database of diagnosis keys against rolling proximity identifiers (RPIDs) on a user’s device — as the API app does — leaves open the possibility that the contacts of an infected person will figure out which of the people they encountered is infected’, EFF wrote.

The risk could be lowered by shortening the time that the diagnosis key is used to generate RPIDs. EFF also warned that API app raises the risk of cyber-attack because there is currently no way to verify the device sending an RPID. As a result, bad actors could collect RPIDs from other devices and re-broadcast them from their own device.

Response on international level

Response on international level

Even though the COVID-19 pandemic is global, the development and implementation of contact tracing apps has taken place only on national levels. However, international organisations have issued sets of guidelines on contact tracing apps and have started their own initiatives involving contact tracing.

The UN Secretary-General

On 11 June 2020 the UN Secretary-General issued the Roadmap for Digital Cooperation, assessing the current state of digital co-operation, including in terms of the COVID-19 pandemic. It outlines the need for accelerated digital cooperation while anchoring it to the political, social, and legal realities of the digital world.

World Health Organization

The WHO has published, ‘Ethical considerations to guide the use of digital proximity technologies for COVID-19 contact tracing (Interim Guidance)’ intended to inform public health programmes and governments on ethical principles, technical considerations and requirements that are consistent with these principles; and how to achieve equitable and appropriate use of contact tracing apps. These principles include time limitation on contact tracing, testing and impact evaluation of the apps, proportionality of data collection, voluntary adoption, transparency, independent oversight, and more.

The WHO also published the classification of digital tools implemented in fighting COVID-19, which include outbreak response tools, proximity tracing tools, and symptom tracing tools.

International Telecommunication Union

The WHO and ITU, with support from UNICEF, created an initiative to work with telecommunication companies to text people vital health messages directly to their mobile phones to help protect them from COVID-19. These text messages aim to reach billions of people that are not able to access the Internet for information.

The ITU has launched the Global Network Resiliency Platform (#REG4COVID) as a place where regulators, policymakers, and other interested stakeholders can share information, view what initiatives and measures have been introduced around the world, and discuss and exchange experiences among peers.

In May 2020, the ITU published ‘First Overview of Key Initiatives in Response to COVID-19’ as a basis for further analysis and discussion papers to help countries in their response to the COVID-19 crisis. In this document, the ITU outlines short and long-term regulatory initiatives in response to COVID-19 as related to network management, customer service, governmental subsidies, easing regulatory requirements for licensing, etc. It also outlines initiatives in individual countries to maintain internet connectivity in cooperation with telecom companies. These include increasing broadband speeds, free services to customers, or additional data allowances.

Another international initiative was adopted by the World Bank, the ITU, GSMA and the World Economic Forum. The ‘COVID-19 crisis response and the digital development joint action plan and call for action’ outlines the need for digital infrastructure and access to secure online services, especially for the vulnerable and unconnected. This action plan aims to increase bandwidth, strengthen resilience and security of networks, connect vital services and ensure the continuity of public services, power FinTech and digital business models, promote trust, security and safety, and leverage the power of mobile big data.