Human-centered design and open data: How to improve AI

28 Nov 2019 10:35h - 11:35h

Event report

[Read more session reports and updates from the 14th Internet Governance Forum]

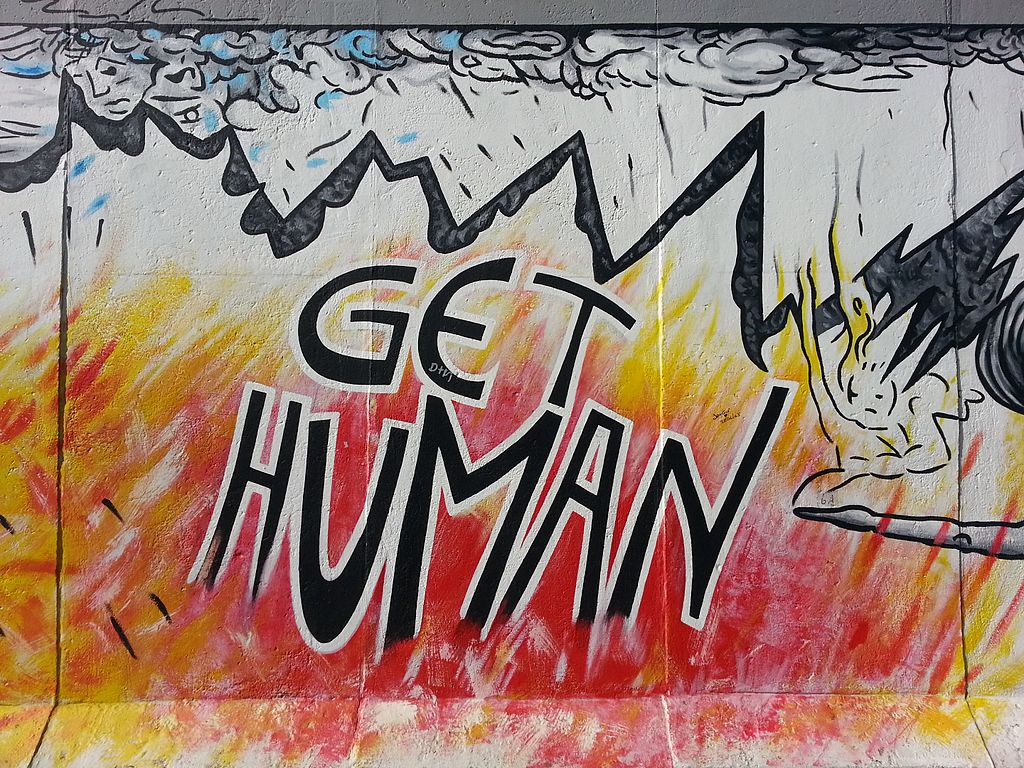

Ms Luciana Terceiro (Economist and Policy Analyst, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)) said that two words that sum up the session are ‘Get Human’ – featured among the Berlin wall graffiti.

What is a humanistic approach in artificial intelligence (AI): spanning issues of open data, open decisions, web technologies, and web design? The session on human-centered design explored how open data principles could help overcome some of the consequences of uneven data concentration and increase its quality. Whether from the Global South or North, the speakers agreed that open standards and the involvement of users in the development of AI systems are key to creating more fair, accessible, and trusting systems.

Mr Diogo Cortiz da Silva (Computer Scientist, University of San Paolo) spoke from the position of software development, iterating that in the development of AI models, experts from professions such as design and humanities need to be involved. While the public focus is often on datasets and biases being built into them, he explained the importance of metrics and how the choice of the variables used can have a significant impact on the results gained from the same dataset.

Being ‘obsessive’ about users, embracing transparencies, algorithms that are as diverse as our population, embedding citizen views in the designed, were some of the ideas put forward by Ms Jaimie Boyd (Chief Digital Officer, Government of British Columbia). She spoke from the experience of running the open data portal of the Government of Canada, seeing it as a learning organisation in a global environment of pressure to innovate, a pressure which is now widely present in the public sector. In order to reflect on the fact that 60% of Canadians feel that laws and government policies are not keeping pace with changes in technology, they developed a tool for gathering real time sentiment analysis of public opinions that was made available through social media.

Their approach includes something that Boyd referred to as data hygiene shipping code early and often, but also imposing on themselves the rigger, the discipline, the culture, and governance to include citizens actively in the whole process of the development of services to adapt to their needs. She offered three main categories of this hygiene. First is having an ‘obsession’ with users, really making sure that services are tested with real people. Second is being agile in not just shipping, but also testing and iterating software. Finally, open data, as well as open source code, is a critical enabler to embracing transparency. Having advisory committees and people analysing algorithms from diverse populations is also critical.

A model that the open data portal of the Government of Canada developed is to require high standards of open data for interoperability, meaning having a clean data source that can be interoperable across national borders. Some of the services the portal has worked on include predictive analytics around bus departures, natural language processing to help identify technical risks in the regulatory process, interactive court services, ability to triage bankruptcy cases when they come into the national regulatory system.

Cultural and social acceptance varies across society and contexts. A recent European Commission report on Central and Eastern Europe, showed that in this area there is a lack of transparency and no use of open data, lessening the amount of faith citizens have in the public sector, in the cases observed. There are several facts that cause this scenario.

One of them is that there seems to be a fanciful belief by governments, that people will just trust machines that come from the government, while the government does nothing to increase the trust in the process. The other is the lack of competencies in the public sector concerning the development, release, and maintenance of software. In this context, the discussion about the human-centred design should involve not only citizens, but also public officials who will actually be using or be responsible for the usage.

Terceiro spoke about the OECD AI principles, as one of the world’s first intergovernmental policy guidelines in AI, drafted by 52 experts, including academic, private sector, labour unions, civil society, the variety of which allowed reaching consensus with the principles. She mentioned they are in the process of launching the OECD AI observatory they will follow on the recommendation by monitoring the implementation of principles.

Whether AI was spoken about from the technical perspective of software development and design, or public administration or global policy AI principles, the speakers brought to the table the importance of advancing inclusion of under-represented populations, human-centred values and fairness in the datasets, methods and development of projects, through open standards, in order to prevent technology in becoming another Berlin Wall.

By Darija Medić

Related topics

Related event