Digital Watch newsletter – Issue 67 – March 2022

Download your copy

Accédez à la version française

SPECIAL REPORT

Up in cyberarms

There are two main ways technology is being (mis-)used in the war between Russia and Ukraine. The first is to bring critical infrastructure to its knees. The second is to use misinformation as part of the arsenal.

Bringing critical infrastructure down

As soon as the Ukrainian crisis escalated into armed attacks, cyberattacks followed. Ukrainian government websites and banks were the first to be hit. Then came the attacks against Ukrainian organisations, troops, and border controls.

Most of these attacks used malware called HermeticWiper, which can wipe out data. It seemed befitting that attackers would employ malware that destroys data, just as armed attacks were destroying physical targets.

Cybersecurity experts analysing the malware have so far said that there is insufficient evidence to attribute HermeticWiper to Russia, but the timing of its deployment was too much of a coincidence to ignore. The phishing attacks against the Ukrainian troops, however, have been attributed to UNC1151 hackers, officers in the Belarusian military.

In response, other actors stepped in to help Ukraine’s IT army stave off the attacks: The EU deployed its Cyber Rapid-Response Team (CRRT) to Ukraine; companies (such as Google and Amazon) pledged cybersecurity support for Ukraine. Hacker groups such as Anonymous launched DDoS attacks against Moscow’s stock exchange, Russia’s Defence Ministry, and the Russian space agency Roscosmos.

What states shouldn’t do, but will do anyway

Just as the conflict continues to escalate, so will the cyberattacks. The latest sanctions – including the suspension of operations in Russia by the SWIFT network, Paypal, VISA and Mastercard – spell more cyber trouble for international banks, which are on high alert.

Recent history tells us the cyberwar will not stop at banks. Even if norms of state behaviour put certain actions off-limits, they did not stop ransomware attacks from crippling electrical grids, food supplies, and hospitals in times of peace – let alone in times of war. Off-limits? Shields up.

A hacking group affiliated with Anonymous tweeted it had ‘shut down the Control Center’ of Russia’s Space Agency Roscosmos. But Roscosmos’ chief denied the reports. Photo: The Control Station of Russia's Space Agency Roscosmos, March 2018 (credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky)

Disinformation raises its ugly head

Although cyberattacks are the most obvious type of weapons, disinformation is just as dangerous and more insidious. It can be deployed in subtle ways, proliferating and spreading across multiple channels, and affecting people en masse.

There are three parts involved in the spread of dis/misinformation:

- the message,

- the messenger,

- and the recipient.

In countering the spread of misinformation, all three need to be tackled.

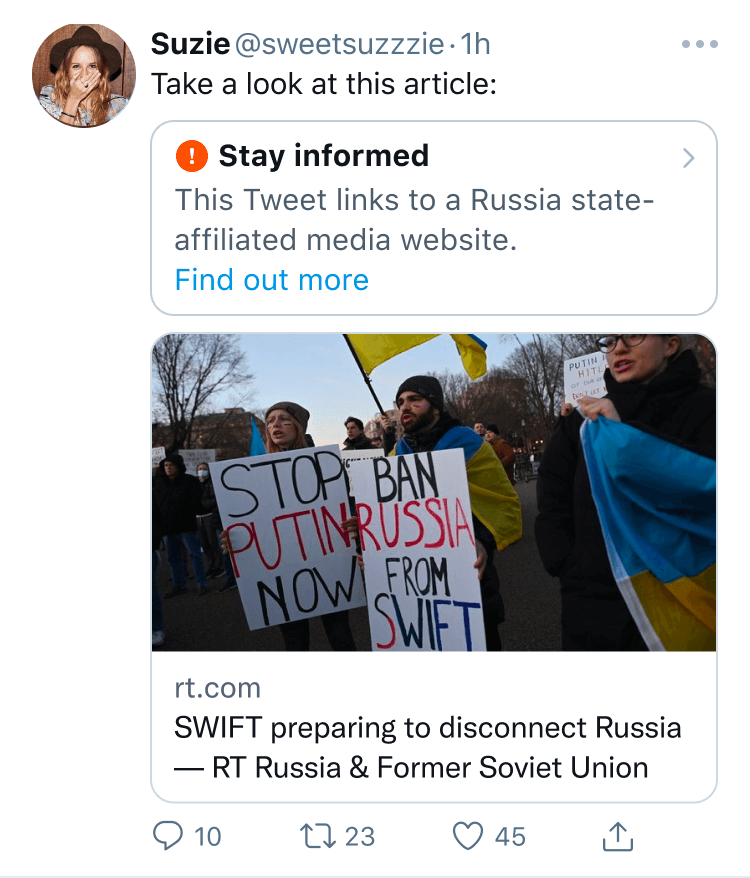

A tweet with a label

When it comes to the message, both sides have accused the other of spreading disinformation. Ukraine and its supporters say Russian state media is generating falsehoods. Russia says the information about the Ukrainian conflict directed at the Russian audience is false and inappropriate. However, by far the largest amount of criticism has been levelled at the Russian state media, resulting, for instance, in it being blacklisted from broadcasting in Europe.

The messenger includes mainstream media (mainly broadcast television) and digital channels (mainly social media, which are also used to stay in touch with families and friends). Unlike the mainstream media, digital channels have the ability to disseminate messages at amazing range and speed, but for many people, television is still the only mass media they can access. The EU’s ban on Russian state media has affected both; actions by the private sector have also involved both.

When it comes to the recipient, disinformation can reach everywhere. This means that anyone can be exposed to false content, and therefore, everyone should have the means to fact-check and to find alternative sources of information. While people in Ukraine (and many other countries) have access to any kind of information they want, people in Russia can only access state-run media while other media channels are blocked. The consequence of being unable to verify information is that disinformation continues to proliferate with ease.

Separating the message from the pipes that carry it

Last week, Cogent Communications, one of the world's biggest handlers of internet traffic, informed some of its Russian ISP customers that it would pause its service. Cogent’s CEO explained: ‘I can't pick good Russian traffic from bad… It's just a big pipe’.

While that may hold true for backbone operators, social media platforms have more knowledge of (and capabilities over) how a message flows through their pipes. Their analytics are extensive: They are able to discern who sees an online post and how everyone else has reacted to it. This means that in practice, social media platforms could decide to target their bans even more precisely (their compliance with the EU’s ban confirms they can) – if they chose to.

For social media companies, this is a double-edged sword: Tolerate the spread of disinformation, and help people stay in touch. Or block content at its source, and risk a government ban on the whole platform. So far, companies have straddled the fence: Apply cautionary labels to specific messages, and hope that access to the platform remains untouched.

It matters little for Facebook and Twitter. Russia’s communications regulator, Roskomnadzor, announced that the country was blocking them.

But it still matters for other social media platforms popular in the region (especially if they also help people stay in touch) and other information-based platforms. They too are facing this double-edged sword, and until Roskomnadzor arbitrates, they too must decide which consequence is the lesser evil.

Actions affecting Russian state-run media, including RT and Sputnik

|

In Russia |

In the EU |

Worldwide |

|

|

Blocking RT and Sputnik channels across Europe |

|||

|

Banning state-run media from advertising |

|||

|

Limiting recommendations of state-run media updates globally |

|||

|

Removing channels/videos for violating community guidelines |

|||

|

Pausing all ads targeting Russian people |

|||

|

Blocking access to RT and Sputnik |

|||

|

Blocking all ads by Russian advertisers |

|||

|

Adding labels on tweets linking to Russian state media |

|||

|

Reducing the circulation of Russian state content on Twitter |

|||

Russia: To block or not to block

It’s easy to get carried away with warmongering thoughts amid reports about civilian casualties and humanitarian corridor bombing. But a request to delete a country from the internet needs some level-headed reasoning.

Just because it can…

When Ukraine’s deputy prime minister requested that ICANN (the organisation which manages the internet’s DNS or address book) cut Russia off from the internet, very few doubted ICANN’s ability to comply, if it decided to.

In technical terms, it could trigger a kill-switch through a unilateral action of the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA). In legal terms, since California has jurisdiction over ICANN, theoretically the USA could order ICANN to take action. And if this did not involve Russia, one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council with veto power, the UN Charter (art. 41) could be invoked to sanction measures taken through ‘other means of communication’.

Doesn’t mean it should…

There are several reasons why Ukraine’s request was turned down. The first is that unilateral action would have destroyed the entire model which took decades to build. There’s an entire structure of accountability, enhanced in 2016, which helps ensure that ICANN and IANA functions are not misused.

The second is that Ukraine’s request wouldn’t have guaranteed that Russia would be entirely cut off. There are parts of the system which are beyond ICANN’s control – parts which could result in a fragmented internet.

The third is that disconnecting a country from the internet is not the answer to countering wrongdoing by that country, no matter how serious these might be. Such an action would mark the beginning of the end of the internet we know of today, which despite all its issues, remains an integrated global public good.

Russia’s intentions for RuNet

What if it’s Russia itself that wants to cut itself from the internet? As implausible as it sounds, it’s possible that the country is already ready and able to go solo. A 2019 test concluded that Russia’s national internet infrastructure, known as RuNet, could function without accessing the global DNS system and the external internet. Reports say the test was carried out again in 2021. An unverified tweet from Belarus-based Nexta is now claiming that Russia will disconnect itself on 11 March.

Regardless of who gives the order, the effects of a disconnected Russia will be the same: a fragmented internet, and an even more isolated people. It would mean that Russians will be unable to get in touch with others beyond their own borders, and that they won’t be able to access information other than what the state wants them to see. If this happens, it would also mean a loss for the rest of the world as well.

IN FOCUS

The State of the US Union: National policy, global impact

The US president’s State of the Union address, delivered (almost) every year, paints a good picture of the country’s priorities and plans for the rest of the year. To what extent will the three digital issues mentioned in this year’s address – semiconductors, digital taxes, and children’s well-being online – affect global digital policy and geopolitics?

Economic nationalism, global competitiveness

US President Joe Biden’s address underlined the USA’s wish to cut off its supply chain dependence on other countries, especially in the semiconductor industry. Semiconductors are a key component in practically every electronic device we possess.

The industry is particularly fragile: The rise in demand for consumer products (blame it on COVID-19) and the disruptions in chip manufacturing (again, blame it on COVID-19) have led to enormous shortages in electronics and a rise in prices.

The chip industry is also one of those sectors which is highly reliant on research and development (R&D). If a company slacks off, it can easily and very quickly be bypassed by other companies using more advanced technologies.

The USA’s ambition can be explained using a simple equation: If the government is able to build more chip factories on its own turf by subsidising their costs, it can reduce shortages in the supply chain and cut its reliance on other countries.

The infrastructure portion of Biden’s address describes what the US government is doing to fulfil this ambition. Chipmaker Intel, for instance, has just started building two foundries in Ohio, to the tune of US$10 billion each.

‘…That means, make more cars and semiconductors in America, more infrastructure and innovation in America, more goods moving faster and cheaper in America, more jobs where you can earn a good living in America. Instead of relying on foreign supply chains, let’s make it in America.’

But even if the President’s ‘made in America’ speech is also a call for US companies and consumers to help achieve this ambition, there’s more to the equation. For instance, there’s serious competition among the world’s top semiconductor manufacturers to produce more technologically-advanced products. Since the technology used by TSMC (a Taiwanese company) and Samsung (a South Korean company) is arguably the most advanced available, the US government’s bets on Intel need to be matched by timely upgrades to the technology Intel is working on.

The EU wants to produce at least 20% of the world’s next-generation chips by 2030. China is also investing heavily in its own production. If China is able to increase its reliance on home-made chips, it would not only reduce others’ market share, but also reduce its own exposure to supply chain delays. Time is not on the US’ side.

Tax them all, but make it quick

The biggest battle in reforming the global tax rules to match modern times ended last year when almost 140 countries agreed on new OECD rules (it’s now a matter of ironing out the technical details and implementing them on the national level).

The new rules are based on two pillars. Pillar I sets out a way to decide which jurisdiction(s) should collect giant multinational companies’ taxes (rather than the jurisdiction where they are incorporated: It will be the countries where they are the most economically active). Pillar II will oblige countries to impose a minimum tax rate of 15% for companies earning more than €750 million in revenue.

The US Congress is currently codifying the rules. Due to technical complications (and computations), the process is stalling. Once again, time is not on the US’ side.

One variable is the midterm elections in November: If President Biden’s party loses one or both houses of Congress, negotiations will stall even further. If things continue to stall in Washington (Pillar One is trickier for the USA), they will also stall at the EU level, despite the EU’s progress (Estonia, Hungary, and Poland want both pillars to be implemented in parallel). What happens – or doesn’t happen – in Washington will, therefore, have a bearing on when the new rules will come into effect.

|

Pillar One |

Pillar Two |

|

Early 2022 – Text of the Multilateral Convention (MLC) and Explanatory Statement to implement Amount A of Pillar One |

November 2021 – Model rules to define scope and mechanics for the GloBE rules |

|

Early 2022 – Model rules for domestic legislation necessary for the implementation of Pillar One |

November 2021 – Model treaty provision to give effect to the subject to tax rule |

|

Mid-2022 – High-level signing ceremony for the MLC |

Mid-2022 – Multilateral Instrument (MLI) for implementation of the STTR in relevant bilateral treaties |

|

End-2022 – Finalisation of work on Amount B for Pillar One |

End-2022 – Implementation framework to facilitate coordinated implementation of the GloBE rules |

|

2023 – Implementation of the Two-Pillar Solution |

|

The OECD’s target deadlines: Are they at stake?

Media platforms’ national experiment

President Biden levelled some of the harshest criticism ever towards social media: ‘As Frances Haugen, who is here tonight with us, has shown, we must hold social media platforms accountable for the national experiment they’re conducting on our children for profit.’

Frances Haugen’s revelations, back in October 2021, rattled Facebook’s reputation to its core, mainly due to the implications for children’s well-being. The thousands of internet documents that the whistleblower leaked to the Wall Street Journal revealed how the company intentionally hid what it knew about the effects of social media on children’s mental health.

In her written testimony, the company’s former employee warned that ‘Facebook chooses what information billions of people see… with control over our deepest thoughts, feelings and behaviors’, which requires urgent oversight.

The US president’s choice of words is both striking and underwhelming. Striking because of the pressure he has imposed on policymakers to take tough positions on anyone conducting ‘experiments’ on children (and it’s worse, he believes, when it’s motivated by profit). Underwhelming because of the suggestion that the experiment was ‘national’, rather than global.

At least this doesn’t negate ongoing child safety policy processes. National and global frameworks concerning children offer strong protections and there’s even more reform coming up, especially in Europe, with the new Digital Services Act slated to become law as early as summer.

BAROMETER

Digital policy developments that made headlines

The digital policy landscape changes daily; here are the main developments from February. We’ve decoded them into bite-sized authoritative updates. There’s more detail in each update on the Digital Watch Observatory.

Global digital architecture

All eyes are on the tragic escalation of the conflict in Ukraine. In parallel to military assault and cyberattacks (see below), state-affiliated media outlets in Russia were banned in Europe, and some Russian banks excluded from international payment systems. More on pages 2-5 and on our dedicated space: Ukraine conflict: Digital and cyber aspects

Sustainable development

Part of the EU’s investment package of €150 billion will go towards boosting digital connectivity in Africa, in the form of submarine (the EurAfrica Gateway cable) and terrestrial (across Sub-Saharan Africa) cables, and satellite-based connectivity.

Security

Ukraine was hit by several cyberattacks, allegedly from Russia; in response, hackers launched attacks on Russian infrastructure.

Right before the Ukrainian conflict escalated, Russia and China reiterated their readiness to cooperate on ‘international information security’.

Looking back at a recent cyberattack affecting the data of over 50,000 vulnerable people, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) explained how ‘The hackers were able to enter our network and access our systems by exploiting an unpatched critical vulnerability… Unfortunately, we did not apply this patch in time before the attack took place.’

E-commerce and Internet economy

There are more trade tensions between India and China: India has blocked 54 mobile apps, mostly Chinese, bringing the number of blocked Chinese apps to 321. China wants India to use the same metric for all foreign tech investors as those applied to Chinese firms.

Antitrust woes for Big Tech continue. PriceRunner, a Swedish provider of price-comparison services, sued Google for allegedly giving preference to its own comparison-shopping services on its search engine. Google was also found in breach of Russia’s antitrust laws.

Infrastructure

The CEOs of Telefónica, Deutsche Telekom, Vodafone, and Orange have called on the European Commission to quickly introduce laws that would oblige content providers (such as companies involved in video streaming, gaming, and social media) to contribute to the cost of the European digital infrastructure.

The EU has launched a €6 billion communications package. This includes a proposed regulation to extend satellite coverage and make satellite communications more secure, and a communication on managing the increasingly crowded satellite space by setting the rules of the road.

Digital rights

New rules proposed by the European Commission will allow users of connected devices to gain access to data they generate, which so far is largely retained in the hands of private companies.

A new lawsuit in Texas alleges that Meta (formerly Facebook) processed biometric data from people’s photos and videos without their knowledge. In parallel, the company will resolve a US$90 million privacy lawsuit from 2012, according to a preliminary settlement filed in California.

Content policy

The UK government is proposing new measures as part of its Online Safety Bill to protect children online, including an obligation for adult sites to introduce stronger age verification measures.

Jurisdiction and legal issues

According to the French data protection agency (CNIL), user data that is collected by Google Analytics and then transferred to the USA is a violation of the GDPR. CNIL said that Google’s measures couldn’t guarantee that the data is safe from the prying eyes of US intelligence services. A similar decision was issued a few weeks ago by the Austrian Data Protection Authority.

New technologies

The OECD has launched a new framework for classifying AI systems, principally to promote a common understanding of what these systems include. The new classification will help explain what the building blocks of AI systems are and what they do in practice.

The US’ ambitions to rely on home-grown supply chains, including semiconductors, was one of the top priorities in President Joe Biden’s annual State of the Union address.

The European Commission has also proposed a package of measures under its new European Chips Act. The aim? The EU wants to double its market share of global chips to 20%.

GENEVA

Policy updates from International Geneva

Many policy discussions take place in Geneva every month. In this space, we update you with all that’s been happening in the past few weeks.

1 February 2022 | 7th Geneva Engage Awards

Every year, the Geneva Engage Awards recognise actors in International Geneva whose social media outreach and online engagement contribute towards a larger footprint for Geneva. Why does this matter? Because the policies discussed and negotiated in Geneva, in areas such as development, human rights, and digital issues, affect millions of people around the world.

The winners of this year’s awards for each of the three categories (international organisations, NGOs, and permanent missions) were: The UN Office in Geneva, GAVI – the Vaccine Alliance, and the Permanent Mission of the USA to the UN.

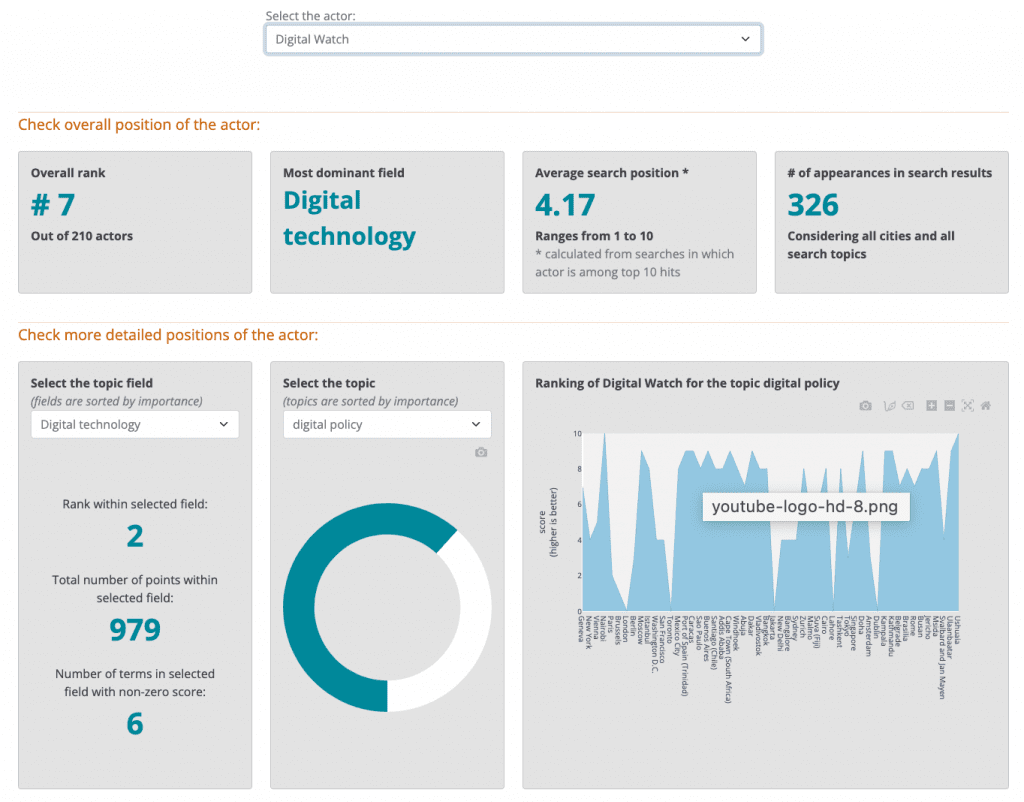

This year, the Geneva Internet Platform – the annual organiser of the Geneva Engage Awards – also unveiled a new tool: An SEO-powered Geneva’s global footprint e-kit, which analyses how far and wide Geneva’s web presence reaches, in the areas of diplomacy and tech policy, through the lens of search engines. Explore the tool.

A screenshot: Digital Watch’s footprint worldwide

9 February 2022 | The path ahead for digital cooperation and achieving the SDGs

The panel discussion, featuring special guest Marina Kaljurand, Estonia’s candidate for the UN Secretary-General’s Envoy on Technology, focused on creating economic and social progress, closing the digital divide, and creating equal opportunities for marginalised groups. The UN envoy’s role is critical to fulfilling the UN Secretary-General’s vision for digital cooperation, in line with the Roadmap for Digital Cooperation and the report on Our Common Agenda.

The discussion, organised by the Permanent Mission of Estonia in Geneva, looked at the unique role the UN and the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) play in discussing and dealing with digital topics globally. While the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the path towards attaining the SDGs in some parts of the world, the response should focus on building the capacities of developing countries, especially in cyber issues.

Ms Kaljurand, currently a member of the European Parliament, called for a reality check, saying that ideological divides can block progress, but connectivity and inclusiveness are issues everyone can cooperate on. Ambassador Benedict Wechsler, head of digitalisation at the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, stressed that sustainable finance is a priority area for the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), the country’s body in charge of international cooperation.

Chengetai Masango, head of the IGF Secretariat in Geneva, said that this year’s IGF will take place in Africa, the region with the highest percentage of youth internet users. Jovan Kurbalija, executive director of DiploFoundation and head of the Geneva Internet Platform, referred to the IGF+ model as a potential digital home for humanity – a place and space where people, especially from developing countries, can raise their digital policy concerns (e-commerce, cybersecurity, etc). He also said the international community needs more substantive participation from small and developing states.

9 February 2022 | Digital risk in conflict mediation: Digital Risk Management E-Learning Platform for Mediators

This event, organised by the CyberPeace Institute (CPI), marked the launch of the Digital Risk Management E-Learning Platform for Mediators, developed by the CPI, the CMI – Martti Ahtisaari Peace Foundation, and the UN Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (UNDPPA) Mediation Support Unit.

The platform will help mediators assess the risks arising from digital technologies and understand the threat landscape.

During the launch, panellists underlined that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the use of digital technologies and hybrid models in the mediation process will likely continue to expand in the future.

UPCOMING

What to watch for: Global digital policy events in March

Let’s look ahead at the global digital policy calendar. Here’s what will take place around the globe. For more events, visit the Events section on the Digital Watch Observatory.

1–9 March 2022 | WTSA-20

Held every four years, the World Telecommunication Standardization Assembly (WTSA) decides on the work programme of the International Telecommunication Union’s Telecommunication Standardization Sector (ITU-T) for the next period, including the structure and leadership of study groups. The approved recommendations and resolutions, although voluntary, shape the future direction of ITU-T. WTSA-20 takes place physically in Geneva, with online participation.

7–10 March 2022 | ICANN73

The ICANN73 community forum will be held onlin, and plans a shorter programme. ICANN73 will provide an opportunity for supporting organisations and the community to discuss different issues concerning ICANN's activity, the management of the domain name system (DNS), new generic top-level domains (gTLDs), registry data services and data protection, and universal acceptance. Ukraine’s request to ICANN (see page 2) is expected to be discussed as well.

15 March 2022 | WSIS 2022

The 2022 edition of the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) Forum, which will be held online, will be themed 'ICTs for Well-Being, Inclusion and Resilience: WSIS Cooperation for Accelerating Progress on the SDGs'. The final week will be held online from 30 May–3 June when ministerial roundtables and policy statements will round up the event.

17–18 March 2022 | Blockchain Africa Conference

The theme of the 8th edition of the Blockchain Africa Conference will be ‘Ready for Business?’. This annual event will be held completely online and will gather practitioners from Africa and beyond who are seeking to harness the opportunities and good practice use cases of blockchain technology in the region.

28 March–1 April | 25th Session of the CSTD

The Commission on Science and Technology for Development (CSTD) is a subsidiary body of the Economic and Social Council and the UN’s focal point for science, technology and innovation. The 25th session of the CSTD will be held in Geneva. The main themes of this year’s session are ‘Industry 4.0 for inclusive development and science, technology’ and ‘Innovation for sustainable urban development in a post-pandemic world’.