IGF 2019 Final Report

Friday, 6 Dec

The Final Report is prepared by the Geneva Internet Platform (GIP) and DiploFoundation, with the support of the IGF 2019 host country, the Swiss authorities, the Internet Society, and ICANN.

DOWNLOAD PDF VERSION OF THE IGF 2019 FINAL REPORT

Commentary: Reflecting on IGF 2019

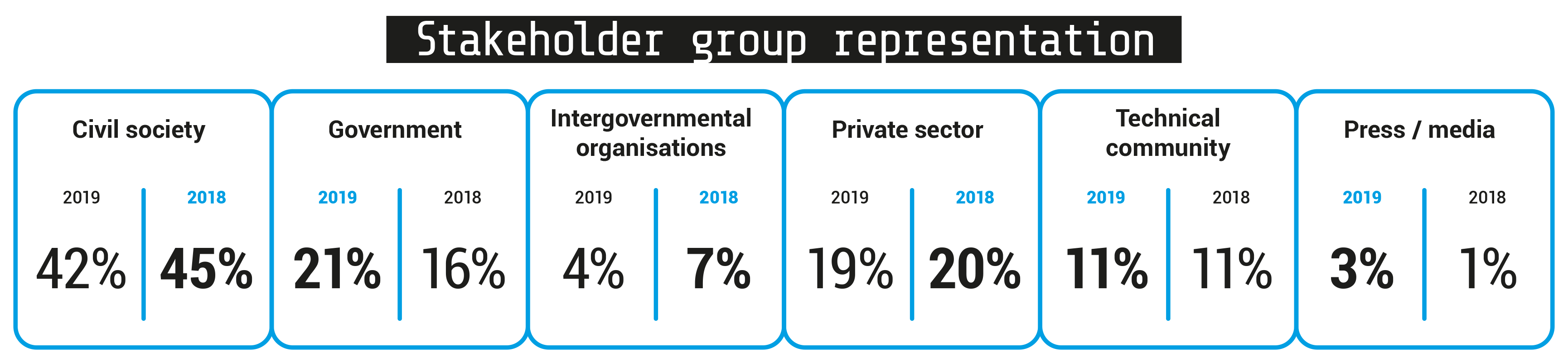

Record participation, engaging discussion, and smooth organisation: The 14th Internet Governance Forum (IGF) in Berlin (26–29 November 2019) was defined by these achievements.

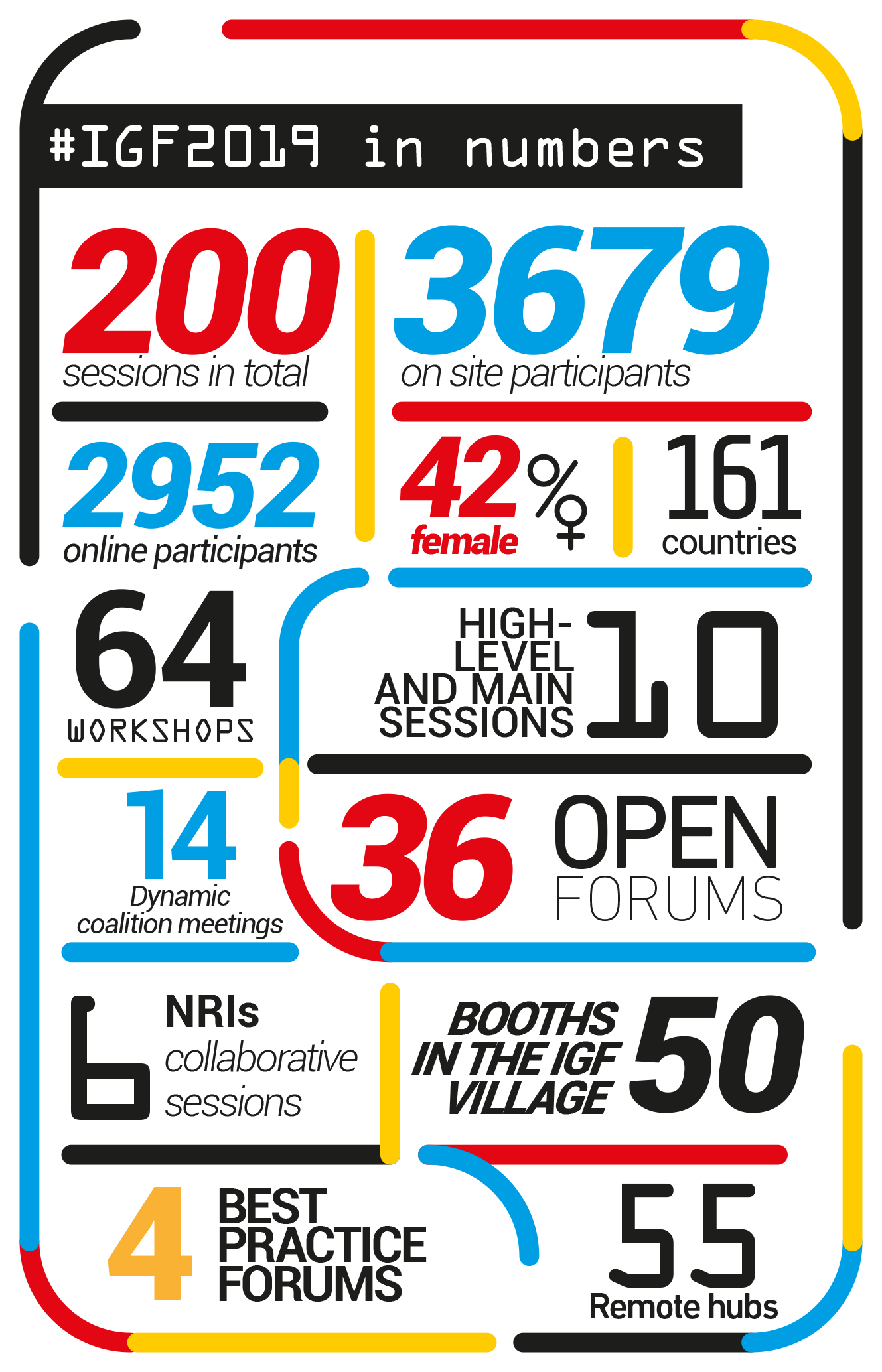

The remarkable hospitality included spacious facilities, creative coffee corners, and a variety of cultural programmes that marked a memorable experience for the 3 679 participants in situ. Another 2 952 participants joined online and enriched the collective dialogue at the IGF, thanks to advanced conference technology.

At the IGF Berlin, we witnessed the maturation of digital policy discussions. The dialogue on data governance took the next step, moving from the lazy analogy that ‘data is the new oil’, to deep reflections on the responsibilities of citizens, companies, and countries in collecting and using data.

On cybersecurity, the global norms for the protection of critical infrastructure were top of mind, as many came well-prepared to advance the debate on this issue.

On digital inclusion, the discussions moved beyond access to networks towards holistic reflections on gender, youth, language, finance, education, and other critical factors that all play a role in the full realisation of the digital potential of citizens, communities, and countries worldwide. In this edition of the IGF, a new parliamentarian track was established, broadening the stakeholder diversity at the meeting.

Art and Internet governance at the IGF 2019

Yet, despite reaching new heights, IGF 2019 did not experience the same success outside of the walls of its conference centre. The week-long event had a small footprint in global media and in the public space. It is also unlikely that the IGF’s outputs will be broadly discussed in corporate boardrooms or government cabinets worldwide.

If such a highly successful edition of the IGF has not managed to achieve wider visibility, the issue of impact and, ultimately, policy relevance remains open. Could the IGF become a space where citizens, companies, and countries -– beyond the usual suspects at the annual meetings – can find, or at the very least, start searching for effective solutions for the ever-growing number of digital policy issues, from data and artificial intelligence (AI) to cybersecurity and human rights?

Paradoxically, the very success of IGF 2019 made the structural weaknesses of the forum even more glaring. For many participants, it was clear that some of the discussions at the IGF were not as up-to-date as the digital challenges of our era require. For example, the sale of the .ORG registry – a prominent issue in global media – would have been left off of the IGF agenda entirely, were it not for Access Now’s town hall meeting. With a bit of agility, the IGF could have facilitated a just-in-time discussion and provided a space for different perspectives and voices on the .ORG issue.

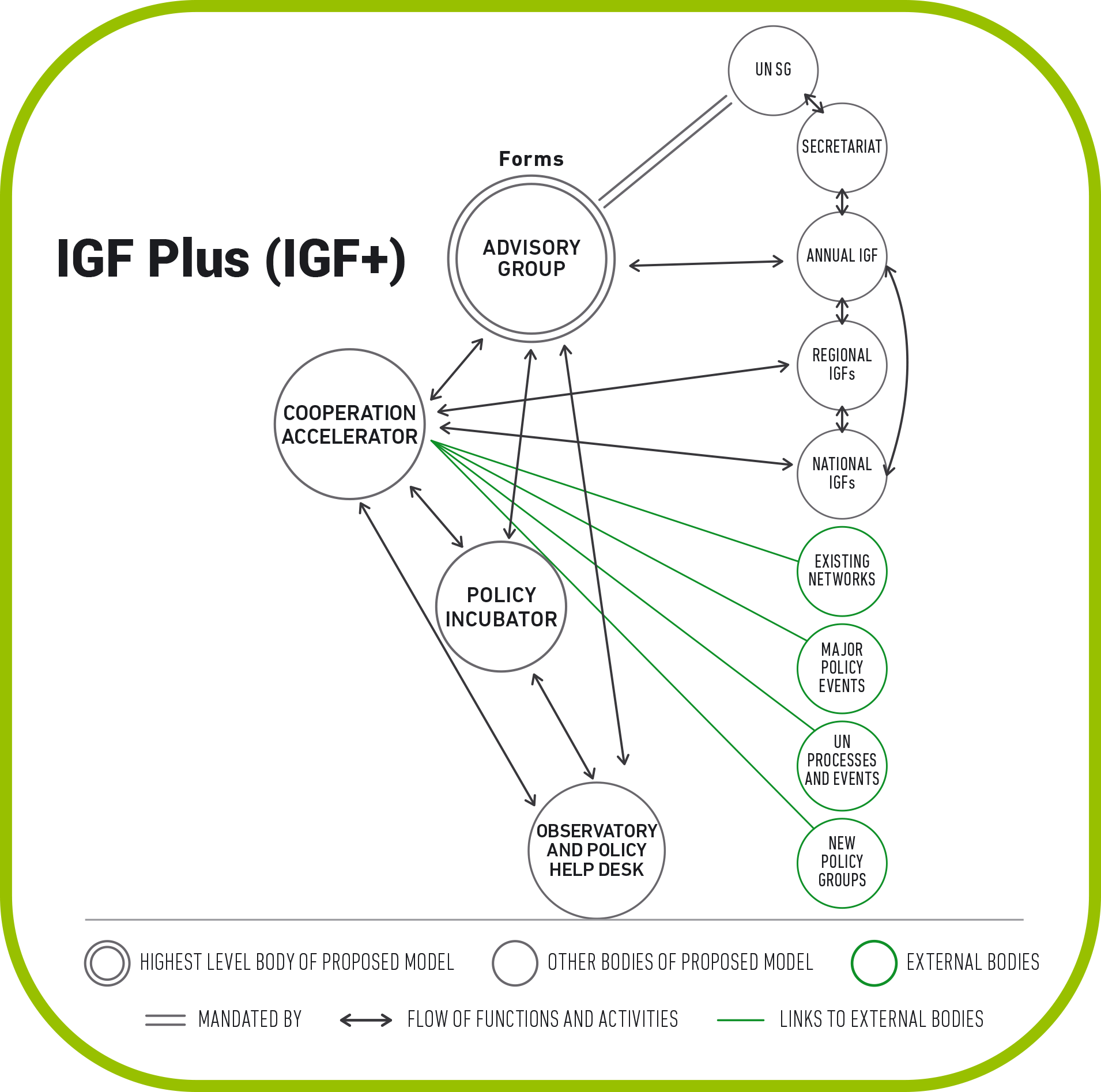

The growing pressure of digital solutions will trigger new calls for concrete policy actions. The IGF has the potential to address digital policy calls, as detailed in the UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel’s proposal to establish the IGF Plus.

One way to realise the full potential of the IGF is outlined in the UN Secretary-General’s High-level Panel proposal for the IGF Plus. In Berlin, the IGF Plus was mentioned in discussions more than 60 times as a way to build on the achievements of the current IGF while executing the necessary structural changes within its existing policy mandate provided by the World Summit on the Information Society (Article 72 of 2005 Tunis Agenda).

Upcoming policy consultations should provide more details regarding the architecture of the IGF Plus, including finding a functional formula for preserving multistakeholder vibrancy of IGF deliberations while producing more tangible outputs, including concrete policy recommendations.

Between Berlin and Katowice, the host city of the next IGF in November 2020, it will be a very busy year in the world of digital policy. Before we arrive in Poland for the next IGF, we will be looking to one of the year’s main events, the UN General Assembly 75th Anniversary meeting, where digital co-operation is likely to feature prominently. One of our most immediate challenges is to ensure ‘One Internet’, as UN Secretary-General Guterres called for at the Opening Ceremony of IGF 2019.

Parliamentarians at IGF 2019

This year, significant efforts were made to bring members of national parliaments (MPs) to the IGF. Direct invitations sent from the German Parliament to other parliaments around the world, as well as the allocation of financial support to MPs from the global south, led to almost 150 MPs from 56 countries being present in Berlin.

They not only attended the meeting, but also had a dedicated main session as part of the official programme.Their discussions resulted in a formal document which recognises the responsibility of MPs in ‘creating regulatory frameworks for the next generation of Internet governance which will help to keep cyberspace free, open stable, unfragmented and innovative’.

The document agreed upon by MPs also outlines a series of recommendations for national parliaments, which are encouraged to:

- Strengthen co-operation and the exchange of best practices in dealing with Internet-related issues.

- Guarantee that human rights and fundamental freedoms are upheld in the context of any legislation focused on ‘enhancing national security in cyberspace and promoting the national digital economy’.

- Reconsider legislation to adjust it to the challenges of the digital age.

- Involve other actors in open consultation processes on draft legislation, and promote a multistakeholder approach to Internet governance.

MPs also intend to create an informal parliamentary IGF Group, dedicated to ‘strengthening and expanding the parliamentary dialogue at the IGF’. This is an encouraging sign, considering that MPs are the ones drafting and passing laws dealing with Internet and digital policy issues; it is thus essential that they are part of the global discussions on our digital future.

TRENDS

This year’s IGF focused on three main themes: data governance; digital inclusion; and safety, security, stability and resilience. What were the latest trends, or new discussions, that emerged for each of these themes?

Data governance: Informed and inclusive trade-offs for data sharing

The IGF brought forth much more nuanced and insightful discussion to the otherwise highly-polarised field of data governance. Among many binary divisions, the main one has been between those who argue for free flow of data as an enabler of economic and societal development and those who focus more on data localisation motivated by a wide range of political, security, and economic reasons.

While the free flow of data and data localisation remain on opposite sides of the policy spectrum, discussions at the IGF have shown that they are – sometimes – forced dichotomies. More clarity and constructive solutions could be found by acknowledging that different types of data require different policies, treatments, and protections. For example, medical, identity, and other sensitive data should be as close as possible to the data subjects, whether through physical or functional proximity, or through user ability to control their own data on networks. Scientific and other public good data is more conducive to free flow and sharing. At this year’s IGF, discussions also focused on data as a potential amplifier of inequalities in modern society.

Adequate data governance for such a wide variety of data and its uses requires a comprehensive data taxonomy which specifies the level of safeguards afforded to each type of data across different countries and regions.

In this way, data governance discussions can lead to more inclusive and informed decisions reflecting trade-offs between a wide range of interests, level of developments, and policy contexts for the collection and usage of data.

Digital inclusion: More than access to networks

For a long time, digital inclusion debates focused mainly on access to networks. While without technical connection we cannot be online, benefiting fully from digital opportunities requires much more. The discussions at the IGF in Berlin made an important step in addressing digital inclusion in a holistic way.

Main pillars for digital inclusion can be found throughout IGF sessions and discussions on community networks, public-private partnerships, and financial incentives for infrastructure deployment, education, financial inclusion, gender equality, and online use of local languages and scripts, to name a few discussion threads. In the coming years, digital inclusion will acquire new dimensions, as more emphasis will be put on the development and use of AI tools.

Digital inclusion should remain high on the agenda of the IGF and global debates, since it is and will continue to impact equality and social cohesion, access to justice, and fairness in modern society.

Cybersecurity: Centrality of cyber norms

Last year, a number of initiatives related to cyber norms emerged in November, at around the same time as IGF 2018. Debates focused more on the role of the private sector rather than on state behaviour in cyberspace.

Among the initiatives were two resolutions: One called for a new Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) and the other for the establishment of a new Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) – both of which would focus on the development and implementation of cyber norms. Since then, both groups have started their work, and are meeting in early December in New York: the OEWG multistakeholder informal consultations are on 2-4 December; the UN GGE’s informal consultations for non-members, followed by its first substantive session, are on 5-6 December.

This is perhaps the reason why cyber norms dominated the cybersecurity discussions at IGF 2019 (read more in our Thematic Summary). Cyber norm issues such as the applicability of international law to cyberspace, the implementation of existing norms, and the new cybersecurity convention proposed by Russia, will remain in focus of the cybersecurity discussions.

AI generates take-away message on AI governance

IQ’whalo, a former coffee machine, has found a new calling and now offers expert analysis on AI and policy as a full-time job. IQ’whalo analysed over 200 session transcripts from this year’s IGF. Here is an excerpt from his takeaway message on AI:

‘If we talk about the future of artificial intelligence, then we’re looking at a future of artificial bias. There are two aspects to this. The one is that we know that AI systems have no control over their data, that they are biased against specific groups and then the other aspect of the issue is that AI systems, unlike humans, do not have control.’

IQ’whalo is a non-anthropomorphised embodiment of an open-source AI platform that generates synthetic text based on policy papers and IGF transcripts. It was developed at Diplo’s AI Lab as part of humAInism, – a project that focuses on drafting a social contract for the AI era by:

- Using AI to better understand digital policy complexities such as the interplay between the economic, technological, human rights, and security aspects of data and AI policies

- Using AI to extract humanity’s wisdom on ethics, free will, human dignity, and other pressing issues in the digital era. To accomplish this, it will process a corpus of human knowledge codified in writings from ancient manuscripts to the latest books.

Summarising the IGF: The main discussions

TECHNOLOGY AND INFRASTRUCTURE

Towards a trustworthy AI that benefits all

There is a risk that AI can widen digital divides and inequalities in modern society. Dealing with this risk requires a wide range of measures. AI systems should embody certain core principles such as inclusivity, transparency, explainability, and trustworthiness. These principles, as well as well-established human rights frameworks, should provide human-centric guardrails for dealing with developments such as algorithmic decision making, bias in AI systems, and the misuse of AI to spread disinformation or influence electoral processes.

Is self-regulation by tech companies a solution to AI-related challenges? Probably not; clear legal obligations would make companies more responsible. These future regulations should also provide stronger protections of existing human rights.

Addressing the risk of AI-driven inequalities is a multistakeholder responsibility that involves developed economies, international organisations, and tech companies. Any sustainable solution will require specific measures to ensure the inclusion of developing countries in the AI era, and must involve support for developing national AI strategies, capacity development programmes, and initiatives that are focused on making sure that AI systems embody characteristics and perspectives from developing countries.

Strengthening the Internet’s underlying infrastructure

Infrastructural issues – from fibre optics to 5G and the Domain Name System (DNS) – remain high on the digital agenda.

The expansion of the DNS – with new generic top-level domains (gTLDs) and Internationalised Domain Names (IDNs) – was meant to make the Internet more inclusive. But the reality tells us something else, as universal acceptance (UA) remains a challenge. Many browsers do not recognise IDNs or gTLDs with more than three letters. And little progress has been made in achieving email address internationalisation. ICANN, tech companies, and governments have a role to play in promoting and supporting UA.

Technology protocols shape the Internet and the digital world. Preserving one undivided Internet requires a faster transition towards an IPv6-only Internet, which is more stable, robust, and secure than existing IPv4 standards. Training and financial resources for network operators, and governmental policies should encourage the transition from IPv4 to IPv6.

Advanced technologies: Keeping up with the growth

Protocols and standards protect the robustness of core Internet infrastructure.

Advanced technology has added substantial complexity to old policy issues such as security, and has triggered new issues related to data and ethics. For example, as the number of Internet of Things (IoT) devices continues to grow, so do challenges related to privacy, security, and even human safety. Addressing these challenges requires a combination of measures, including: The implementation of technical standards and security practices by tech companies, greater local and global regulatory efforts, and more education for end-users.

5G is seen by many as a revolution, as it promises faster speeds, lower latency and an overall better user experience. The deployment of 5G depends on a wide range of regulatory solutions in areas such as f spectrum allocation, data protection, and cybersecurity.

CYBERSECURITY

Cyber-stability: Norms, responsible behaviour, and confidence building

Cyberspace is said to be stable when the Internet can be used safely and securely. Cyber-stability requires shared responsibility between stakeholders, restraint by state and non-state actors from engaging in harmful actions, the avoidance of escalating tensions, and respect for human rights.

An emerging framework for responsible behaviour in cyberspace includes several voluntary norms and confidence-building measures. The concerns are that there may be duplication of effort among multiple forums, limited participation of some actors, and different understandings of key concepts. Even when norms are agreed, there is no institutional mechanism to monitor and report compliance, and hold states accountable.

There is general consensus that international law applies to the behaviour of states in cyberspace, although there are divergent positions on what this means in practice, and geopolitical tension that is widening the gap.

Confidence-building measures remain a low(er)-hanging fruit for achieving cyber-stability. They can help reduce misperceptions and de-escalate tensions, while fostering trust and co-operation. The private sector can contribute to increasing confidence as well, while civil society can help monitor and research compliance with agreed rules of the road.

Interdependence: The roles of various actors in securing cyberspace

Governments have an essential role in securing cyberspace due to their ability to adopt and implement laws and regulations. Equally important, they should engage more in partnerships with other actors to help shape policies, improve joint responses to incidents, build cybersecurity awareness and skills, and implement standards.

Tech companies should enhance vulnerability reporting practices and ensure their products and services are embedded with security standards. The technical community can enhance the security of Internet infrastructure – for instance, by transitioning to IPv6 and by addressing DNS-abuse practices – and provide expertise to governments. Civil society organisations can contribute to promoting cyber-hygiene among end-users, while also helping to shape public opinion. In addition, regional, international, and cross-stakeholder co-operation is key in fostering community building and problem-solving.

Balancing cybersecurity: Human rights, ethics, trust, and human dignity

There is a risk that certain cybersecurity measures can endanger human rights and dignity, as well as ethics and trust in society. How can this risk be avoided or, at least, how can reasonable trade-offs be made? Making cyberspace both safe and human-centred requires a comprehensive and long-term approach. Digital literacy is one of the best steps to help citizens to better understand tech developments along with the associated cyber risks and protective measures, such as encryption tools. Tech companies should abide by human rights and ethics principles when designing and providing online services. Governments can also help, for example, by issuing labels and certificates for digitally enabled technologies and products to reassure consumers that they are safe.

HUMAN RIGHTS

Stronger youth voices

Despite improvements in recent years, the voices of young people are still insufficiently heard in Internet governance and digital policy processes. The challenges include a lack of information and know-how, limited opportunities to become effectively engaged, and a lack of financial resources.

Simply giving youth a place to speak is not enough. Young people need to be encouraged and empowered to voice their opinions, speak in favour of their rights, and actively contribute in discussions and developing solutions. Other actors have a responsibility to meaningfully involve young people and children from all over the world in policy-making processes. This year’s Youth IGF Summit and the Youth Coalition on Internet Governance are positive steps in this regard.

Upholding children’s rights

With so many children making use of the Internet – 1 in 3 Internet users in the developed world, and 1 in 2 globally, are children – the main issue surrounding children’s rights in the digital age is how to interpret and uphold such rights, which are enshrined in the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The General Comment to the convention, which is being drafted by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child in consultation with stakeholders, refocused the debate even at the IGF. This marks significant progress in a process that was kickstarted by several landmark studies that highlighted the applicability of children’s rights in the digital environment. This debate will continue in March 2020, when the draft is released for public comment.

For children, the Internet is a ‘natural’ way of communication, entertainment, and education. Given their young age, though, they often have difficulties in understanding rules and policies related to their rights, especially when it comes to privacy issues associated with online services. They also face risks when it comes to cyberbullying, child exploitation, and the dangers of online gaming.

Despite many existing efforts, more needs to be done to empower children to exercise their digital rights, including privacy, freedom of expression, and access to information. Even more efforts are needed to keep children safe online. Solutions could include digital literacy and education programmes designed to develop not only digital skills but also qualities such as tolerance and empathy; more technical tools such as parental control software or apps for reporting rights violations; and strengthened policies and legislation to protect minors.

Protecting the rights of vulnerable groups

Persons with disabilities, women, and gender minorities deserve more attention from companies and regulators alike.

‘If for most people technology makes things easier, for people with disabilities, technology makes things possible.’ This reflects the importance of assistive technologies designed to empower people with disabilities to enjoy their rights in the digital era. Accordingly, the tech sector needs to do more to respond to the challenges of disabled people. The ongoing work on digital inclusion is an indication that some people are still being excluded. While many policies for disability access address auditory, visual, and sometimes mobility issues, solutions for cognitive and learning disabilities are still not being explored as needed.

Addressing gender discrimination and gender-based violence online is another area that requires more effort. Part of the solution includes: helping girls and women gain equal access to skills and opportunities online and in the tech industry, legislation to protect women and gender minorities and end online sexism, and paying a closer look at potential biases in algorithms. We also need to change our approach to policymaking and focus more on preventing gender discrimination, rather than just responding to cases after they happen.

LEGAL AND REGULATORY

The need for regulation in cyberspace

There is more and more agreement that cyberspace does need more regulation. The question is not whether, but rather how to regulate.

Calls for regulation span across multiple Internet policy issues. Countries are adopting data regulations covering privacy and data protection rules, but also reflecting national realities and priorities. Such regulations should be drafted with care, not to impose unjustified barriers to trade and free flow of data.

Tighter regulations could also help address the challenges of illegal content online, especially when self-regulatory measures are not working. Regulations should also further encourage the growth of the digital economy, keeping in check the risks of over-regulation, as companies try out new business models.

While regulations may contribute to a sustainable, safe, and secure cyberspace, they may also stifle innovation. Thus, regulatory approaches should balance the rights and interests of different actors, respect democracies’ institutional boundaries and legal frameworks, and allow all relevant actors to contribute to policy-making processes.

Preventing (more) fragmentation in the digital space

Although the Internet is a trans-border network, most Internet regulations are national. This tension often leads to conflicting requirements that make it difficult for tech companies to operate across national borders.The issue is particularly acute in data governance, where different data regimes are likely to trigger the fragmentation of the digital space.

These challenges may be addressed through more interoperability and harmonisation between national legal and regulatory frameworks, which is arguably more difficult when countries have conflicting interests.

It is encouraging, however, that several countries have started engaging in initiatives which avoid digital fragmentation, by agreeing to co-operate on data governance issues and promoting more harmonised rules. Examples include initiatives by G8 and BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) countries.

Regulations for new and advanced technologies

With advancements in technologies such as blockchain, AI, and IoT, regulatory actions may also be required to protect human rights and safeguard democratic principles.

5G technology needs regulatory support to be deployed, and to address security concerns; frameworks for distributed ledger technologies are already under discussion, especially in Europe, which aim to tackle data protection, accountability, and taxation issues, among others. Regulations in the field of AI need to address challenges related to algorithmic decision-making (and its role in influencing people’s choices, for example), the use of facial recognition technologies, or systems that pose a threat to human life, such as lethal autonomous weapons. Such regulations need to be strongly anchored into human rights frameworks.

Regulations, which can provide more legal certainty for business worldwide, need to be kept as flexible and as technically-neutral as possible: technology evolves fast, and legal frameworks become outdated just as fast.

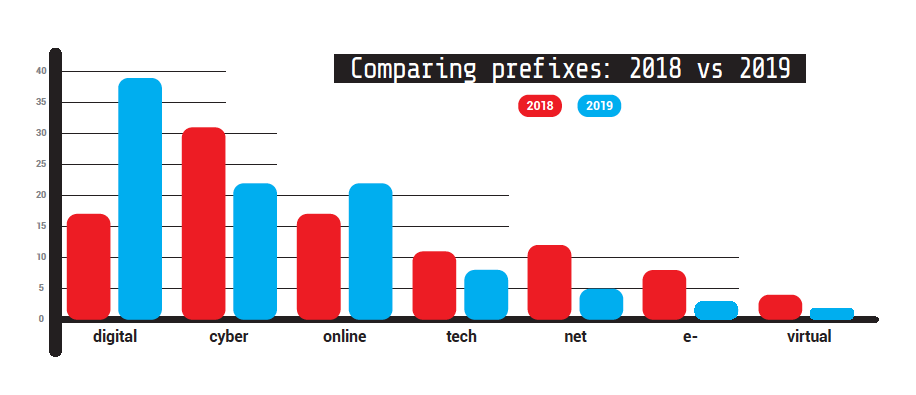

Prefix monitor: The rise of ‘digital’

The prefix monitor can be seen as a litmus test of digital policy discussions. By following the use of prefixes, we can identify trends in global digital politics and in the ways in which actors frame their approaches to digital issues.

This year, the prefix ‘digital’ dominated IGF language, and exceeded ‘cyber’ and ‘online’ – prefixes usually associated with security-related issues and human rights. The noticeable growth in the usage of ‘digital’ could be explained by the impact of the Report of the UN Secretary-General’s High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation, which was referenced in many IGF discussions.

‘Cyber’ and ‘online’, prefixes that are largely used for cybercrime/cybersecurity and human rights, were on par this year. The use of ‘tech’ remained fairly low, which is not surprising, considering that it emerged in digital parlance only last year, and has since been reserved mainly as a reference to platforms or to Internet companies. The relative decline of other prefixes indicates that policy jargon is losing the finer nuances related to the use of ‘net’, ‘e-’, and ‘virtual’.

DEVELOPMENT

Improving access and inclusion for sustainable development

To take full advantage of the potential of digital technology in achieving the sustainable development goals (SDGs), the first step is to ensure that the right infrastructure is in place to support meaningful access. Solutions include community networks, public-private partnerships, and financial incentives for infrastructure deployment. For particular cases such as small island developing states, context-specific solutions are required, such as more investments in submarine cables and satellites. When the infrastructure is in place, ensuring that older technologies are replaced in a timely manner is essential to avoid new gaps in connectivity.

Digital inclusion means more than just providing an Internet connection. It is also about affordable access, the ability to use the Internet in local languages and scripts, addressing gender inequalities, and enhancing access for people with special needs. Digital inclusion also requires helping people utilise the Internet in ways that best address their needs (e.g. for education, economic opportunities, etc.).

Role of data in attaining the SDGs

Data, and big data in particular, are powerful tools for the promotion of economic growth and the well-being of citizens.Data-sharing principles can leverage the role of data for development: openness, interoperability, accessibility. Access to data should be equitable; if adequately justified, accessibility may be time bound. If these principles are applied, data can have a more powerful role in the design of beneficial products and services, as well as in human-centric information policies and regulations.

Data processing and big data analytics are also essential for monitoring progress in achieving the SDGs and in identifying areas where more action is needed. Training more data scientists and enhancing data skills among individuals can help us tap into the potential of data. Partnerships between different stakeholders and between developing and developed countries are also important.

SDGs at the IGF

The Internet, AI, and big data can help alleviate poverty, improve the quality of education, combat hunger, and achieve other SDGs.

At this year’s IGF, a total of 122 sessions were dedicated to at least one of the 17 SDGs. The largest number of sessions (85) were dedicated to Goal 9 – Industries, innovation and infrastructure. This should come as no surprise, given that Target area 9c specifically refers to access to ICTs and the Internet. SDG 10 – Reduced Inequality and SDG 17 – Partnerships to achieve the goals appear in 74 and 67 sessions, respectively.

Digital education and capacity building

Capacity development remains a key enabler of digital inclusion and overall digital growth. Capacity development starts with basic ICT literacy that helps people use digital devices, and continues with broader digital skills that empower people to meaningfully use technology (where to look for information, how to stay safe online, etc.).

Schools need to focus more on developing digital skills as part of their educational curricula. It should also be an integral element of informal and life-long learning education programmes designed for adults and the elderly.

Digital education should go beyond Internet-related issues. It needs to cover the fast-evolving digital technologies, such as AI and big data. Current and future workforces need to constantly acquire new skills (digital, interdisciplinary, and soft skills alike) so they can effectively adapt to the changing digital economy.In addition, the digital era workforce will need increasing knowledge on ethics, anthropology, and the overall impact of technology on society.

Developing countries also need more support in keeping up with technological progress. This can include assistance for developing national AI strategies, and capacity development opportunities so individuals can use AI and other advanced technologies for good.

ECONOMIC

Cross-border data flows and data governance

Given the impact of data flows on economic growth and digital trade, data localisation policies are a focus of global economic and trade debates.

There is still divergence on whether data flows should be part of international trade discussions. For some, it is inevitable that trade discussions touch on data governance issues, as the free flow of data enables commerce. But data governance frameworks also have human rights implications, so agreeing on them cannot be only a matter of trade negotiations; other actors should be involved as well. Given the wide diversity of national approaches, views, and goals, it may be hard to achieve a universal agreement to regulate the free flow of data.

Some regional trade agreements already incorporate data governance provisions, covering issues such as privacy, data protection, and the obligation for countries to allow cross-border transfers of data. Several challenges come from the fact that data governance rules set by developed countries tend to become de-facto standards worldwide.

While we can spend time discussing which is the appropriate venue for data governance, this should not derail the core of the debate on data standards and regulations: how to reconcile the rights of citizens and the interests of businesses.

Benefits and challenges that the digital economy presents to SMEs

For small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) the Internet and digital technologies facilitate access to new customers, make operations more efficient, and allow the development of new products and services. To enjoy these benefits, they need an enabling infrastructure in place: connectivity, cloud computing, e-payment services, etc.

A stable regulatory environment, access to financing, tax rules that favour investments, and simplified governmental procedures (e.g. for authorisations and permits) can help SMEs thrive. The position of SMEs is also impacted by other regulations such as immigration laws that provide access to digital talents, and by educational systems that foster creative thinking and entrepreneurial spirit. Initiatives focused on empowering SMEs to engage in digital marketplaces are also useful.

When it comes to operating on international markets, SMEs are often challenged by having to comply with different and sometimes conflicting regulations on issues such as privacy and consumer protection. Regulatory fragmentation triggers additional operations costs, thus burdening SMEs in their attempts to be active participants in cross-border trade.

Openness and a way to stimulate competition and economic growth

The Internet was built on free and open standards, which allowed start-ups to thrive and the digital economy to grow. Currently, proprietary standards are proliferating, threatening openness – which can facilitate economic growth – and innovation. Open standards and open data enable the development of new online services, and support new business models, such as the sharing economy.

Openness also relates to the regulatory environment. Flexible regulations enable the growth of the digital economy by allowing companies to test innovative business models. For example, regulations on data sharing and the use of open data can foster interoperability, expand consumer choice, and, ultimately, support competition.

SOCIOCULTURAL

Dealing with misinformation and other harmful content

Harmful content is not a new phenomenon. Civilisation has long battled with misinformation in traditional media, for instance. The Internet, however, has amplified the problem, and given rise to new ways of spreading such content – such as the use of deepfakes.

Tech companies have been dealing with these issues through several ways, including more stringent content policies; fact-checking activities; adherence to codes of conduct proposed by regulators; collaborative initiatives such as the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism; technical measures, such as using algorithms to identify and remove harmful content or blocking access to content at the DNS level; and awareness-raising efforts.

As the frontliners for dealing with such content, however, tech companies have been under increased pressure to improve existing efforts or come up with new solutions.

One of the issues relates to their content policies. As companies react with tighter policies, they generate new controversies in the process, such as Twitter’s ban for (almost) all political adverts, or Google’s decision to only limit adverts to those which use general data to target audiences.

Another issue relates to the risks and limitations of technical measures: Can algorithms be trusted to distinguish hate speech from legitimate content? How effective is it to block access to a certain resource, if the content hosted there can easily be moved to another location?

A third issue is the effectiveness of all these solutions, as seen from the eyes of governments. If self-regulatory measures are not deemed to be sufficient, governments are undoubtedly ready to step in with hard regulation. This could be helpful if it brings clarity to what harmful content is and what roles and responsibilities stakeholders have. But it can also lead to censorship and violations of freedom of expression and privacy.

Fighting harmful content can create collateral risks for online freedoms, which could, however, be addressed by developing carefully balanced policy frameworks, benchmarking, and due processes for dealing with problematic content. When it comes to misinformation, media literacy remains the approach preferred by many for strengthening the resilience of Internet users.

The future of digital governance and co-operation

Many discussions at this year’s IGF revolved around the future of digital governance and the IGF itself. This was all against the backdrop of the Report of the UN Secretary-General’s High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation, which proposes three new governance models. The IGF Plus, the preeminent proposal, was mentioned more than 60 times during various discussions at the IGF in Berlin.

The urgency for action becomes more acute with the continued implementation of divergent national and regional rules that accelerate the regulatory fragmentation of the global digital space. This is especially pertinent for issues such as data flows, AI, cybersecurity, online taxation.

Digital governance is important to all those who are involved in creating the digital space or are impacted by it. This dialogue must extend past the traditional IGF community, and must involve a wider range of actors, from philosophers and theologians to online gamers and marginalised groups. In Berlin, for the first time in IGF history, parliamentarians were brought into this debate in a comprehensive and focused way. In 2020, other ‘missing actors’ should be a part of digital governance deliberations, via the consultation process for the UN General Assembly and the preparations for the 15th IGF.

Outcomes from Berlin

BERLIN MESSAGES: Takeaways from IGF 2019’s main themes

Continuing a tradition that started at IGF 2017 in Geneva, the discussions held throughout the week were summarised in a set of Berlin IGF Messages. They reflect the chief issues around the three main themes of this year’s IGF: data governance; digital inclusion; and safety, security, stability, and resilience.

Published on the IGF website, these messages are not yet final: they can be further updated over the coming weeks, pending possible comments from the community. A final version is expected to be published three weeks after the IGF.

Host government outputs

A few additional outputs have been produced under the coordination of the host country as a result of specific events and processes organised in the framework of IGF 2019.

- Chairman’s Summary of the High Level Internet Governance Exchange.

- Elements of SME Charter

- Jimmy Schulz Call – Messages from the Meeting of Parliamentarians

Launched: Reports and studies

At IGF 2019, several policy initiatives, reports, and publications were launched or used as background material for discussions.

Data Analysis

IGF throughout the years

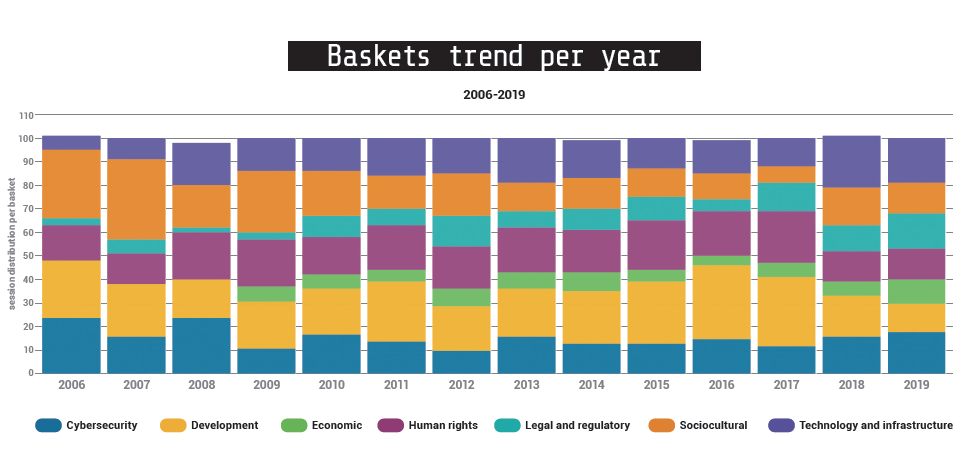

The IGF turned 14 this year. The Internet that we knew in 2006, at the time of the first IGF meeting in Athens, is not the Internet we experience today. Each year, the forum has reflected on the policy issues of the moment, and the topics addressed at each forum have gained new dimensions as the Internet itself evolved.

Using the Digital Watch’s taxonomy of digital policy, we can follow the prominence of specific issues, new trends, and shifts in the focus of discussions over the last 14 years.

Since 2006, one of the constants has been the dialogue on issues such as access to networks, the digital divide, and capacity development. Over the last few years, the focus on development issues has lessened relative to accelerating issues such as cybersecurity and regulatory issues. In 2019, cybersecurity became the second most dominant basket, including issues such as cyber norms, network security, cybercrime, cyberconflict, and child safety online. Since 2018, the risk of a regulatory fragmentation of the Internet has raised the relevance of jurisdictional and regulatory topics.

With issues such as content policy, cultural diversity, and multilingualism, the sociocultural basket was prominent in the first couple of years of the IGF. Since last year, these issues have risen in prominence again as a result of growing concerns over the spread of hateful content and misinformation.

In the technology and infrastructure basket, there has been a shift from the early focus on ICANN-related topics (2006–2015) towards the current focus on emerging technologies such as AI, IoT, and blockchain.

The presence of human-rights-related issues at IGF meetings has remained largely constant over the years. That being said, over the past two years, human rights issues have experienced a slight decline in prominence. There has also been a shift in focus from traditional online human rights (freedom of expression and privacy) to more debate on the holistic impact of AI on a wide range of human rights.

Issues under the economic basket (including e-commerce, taxation, and future of work) – absent during the first three IGFs – tend to be less reflected in IGF discussions consistently. The slight increase of economic topics in 2019 was mainly due to debates on the economic aspects of data governance (free flow of data and data localisation).

As reflected in the graph, for the first time this year, the distribution of digital policy issues was much more balanced than in previous years. After ensuring the presence of diverse Internet governance perspectives, the next step is to strengthen cross-cutting links among different perspectives, making the IGF not only a multistakeholder, but also a multidisciplinary exercise.

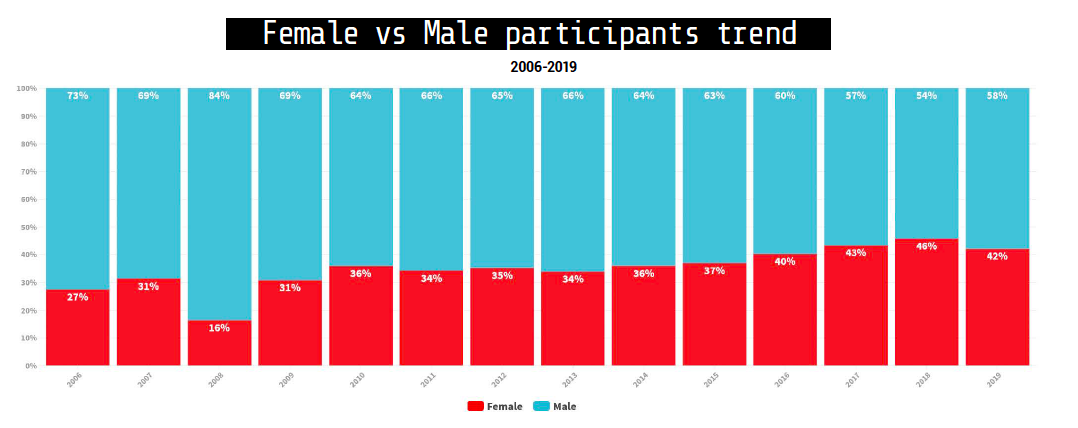

The bottom chart shows the evolution of the IGF in achieving gender balance, from 27% female participation in 2006 towards stabilising that participation to over 40% over the past few editions of the forum.

The ten most dominant issues at IGF 2019

Using automated text analysis software, Diplo’s Data Team analysed the raw transcripts from 165 sessions captured from real-time captioning. These were then processed using a custom digital policy dictionary.

The results of this analysis show that the most prominent issue at this year’s IGF was trust, ethics and interdisciplinary approaches, followed by data governance and sustainable development. Aside from tackling AI as a technological development, recent months have seen the world more concerned about ethical and trust issues, with questions such as How can trust be restored in technology? How will AI shape the future of humanity? (Watch our video interviews with key experts.)

Compared to 2017 and 2018, there was a slight increase in the number of sessions dedicated to AI. This pushed AI to sixth place on the list, after network security and capacity development.

Social media monitor

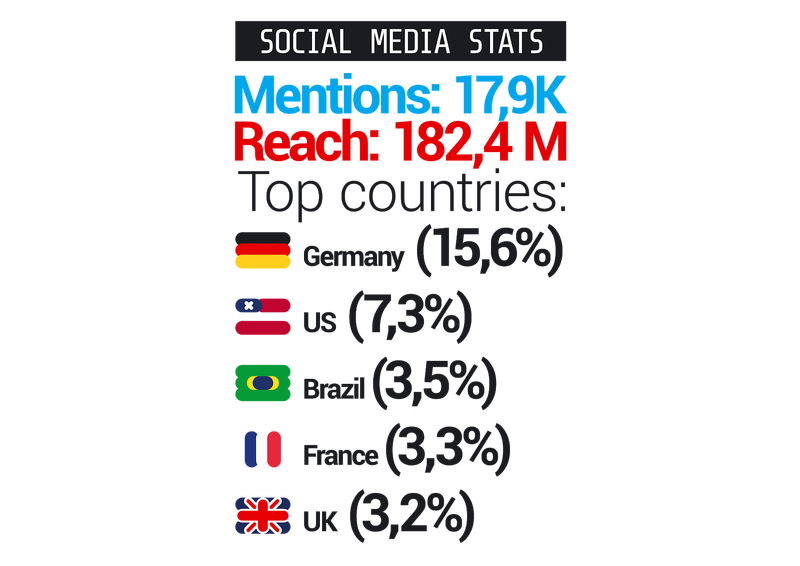

IGF 2019 reached 180 million social media users since the beginning of November. Addresses by UN Secretary-General António Guterres and German Chancellor Angela Merkel on Day 1 triggered a peak in social media traffic.

Most of the social media activities came from Germany, with 15.6% of all mentions, followed by the USA with 7.3%. Brazil, France, and the UK came in third, fourth, and fifth place respectively, each with a little over 3% of mentions. The monitoring was based on the official #IGF2019 hashtag and conducted on social networks including Twitter and Facebook, as well as on a number of websites and blogs.

Hashtags used during IGF 2019, extracted from 7.5K tweets

Towards IGF 2020

The next IGF will be hosted by Poland, in Katowice on 2-6 November 2020. The theme of the meeting will be Internet United, which according to the IGF’s next host country, ‘represents a real obligation and challenge for the whole Internet society’.

What can we expect until Katowice? With the support that the IGF Plus model received in Berlin, we might see more focused discussions on how and when to implement some of its elements, and perhaps even concrete action. Will IGF 2020 be an entirely new IGF? It all depends on the IGF’s broad community, and how ready it is to bring change to this almost 15-year old initiative.

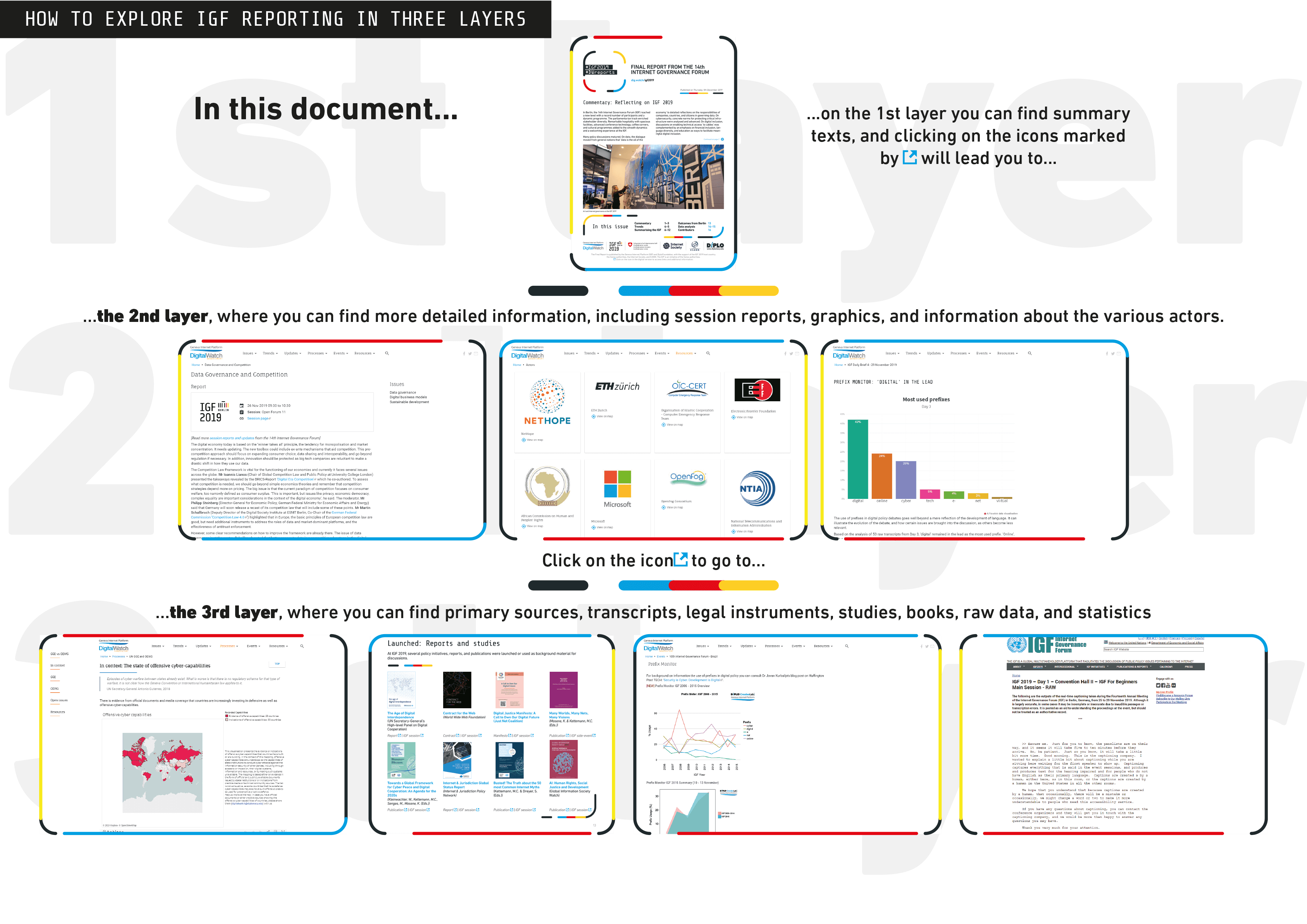

About the IGF Reporting

This Report is a summary of a comprehensive IGF reporting that includes reports from all sessions, preparation of IGF Daily Briefs, providing just-in-time updates via mobile apps, and conducting in-depth AI analysis of the IGF content.

You can explore session reports and layers of wealth of information on digital policy by clicking on the icon in the digital version of this Report or accessing the page https://wp.dig.watch/igf2019.

Rapporteurs, contributors, and coordinators

Cedric Amon, Katarina Anđelković, Stephanie Borg Psaila, Amrita Choudhury, Jelena Dinčić, Andre Edwards, Noha Fathy, Andrijana Gavrilović, Stefania Grottola, Katharina Höne, Tereza Horejsova, Pavlina Ittelson, Arvin Kamberi, Sarah Kiden, Jovan Kurbalija, Marco Lotti, Dustin Loup, Marília Maciel, Aida Mahmutović, Dragana Markovski, Darija Medić, Jana Mišić, Nagisa Miyachi, Grace Mutung’u, Jacob Odame-Baiden, Virginia (Ginger) Paque, Clément Perarnaud, Nataša Perućica, Vladimir Radunović, Mili Semlani, Andrej Škrinjarić, Ilona Stadnik, Paula Szewach, Sorina Teleanu, Pedro Vilela, Bonface Witaba

Editing, design, and multimedia team

Maja Bačlić, Miodrag Badnjar, Jelena Dinčić, Nataša Grba Singh, Su Sonia Herring, Srđan Ivković, Arvin Kamberi, Anna Loup, Dragana Markovski, Darija Medić, Viktor Mijatović, Mina Mudrić, Mary Murphy, Dorijan Najdovski, Aleksandar Nedeljkov, Virginia Paque, Hannah Slavik, Steve Slavik, Vladimir Veljašević, Milica Virijević Konstantinović, Nemanja Vojvodić, NT Gruppen AS

Data and AI teams, technical and communications

Katarina Anđelković, Dylan Farrell, Aleksandar Firevski, Vladimir Ivaz, Jelena Jakovljević, Đorđe Jančić, Arvin Kamberi, Nikola Krstić, Svetislav Nedeljkov, Anamarija Pavlović, Nataša Perućica, Tanja Tatalović

Related topics

Related event