Snapshot: The developments that made waves

AI governance

Chile introduced an updated national AI policy along with new legislation to ensure ethical AI development, address privacy concerns, and promote innovation within its tech ecosystem. In South Africa, the government announced the formation of an AI expert advisory council. The council will be responsible for conducting research, providing recommendations, and overseeing the implementation of AI policies in the country. Meanwhile, Zambia finalised a comprehensive AI strategy aimed at leveraging modern technologies for the country’s development.

The highly anticipated second global AI summit in Seoul, secured safety commitments from leading companies, emphasising the importance of collaborative efforts to address AI-related risks.

In the USA, lawmakers introduced a bill to regulate AI exports. This bill aims to control the export of AI technologies that could be used for malicious purposes or pose a threat to national security. Additionally, the US Department of Commerce is considering new export controls on AI software sold to China. This comes as the USA and China met in Geneva for discussions on AI risks.

Concerns about AI safety and transparency were highlighted by a group of current and former OpenAI employees who issued an open letter warning that leading AI companies lack the necessary transparency and accountability to prevent potential risks.

Technologies

The USA is set to triple its semiconductor production by 2032, widening the chipmaking gap with China. Chinese AI chip firms, including industry leaders such as MetaX and Enflame, are downgrading their chip designs to comply with the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s (TSMC) stringent supply chain security protocols and regulatory requirements, raising concerns about long-term innovation and competitiveness. South Korea has unveiled a substantial 26 trillion won (USD$19 billion) support package for its chip industry, while the EU Chips Act will fund a new chip pilot line with EUR2.5 billion. Japan is considering new legislation to support the commercial production of advanced semiconductors.

Neuralink’s first human trial of its brain implant faced significant challenges as the device’s wires retracted from the brain, affecting its ability to decode brain signals.

Cybersecurity

High-level talks between the US and China brought attention to cyber threats like the Volt Typhoon, reflecting escalating tensions. US and British officials underscored that China poses a formidable cybersecurity threat. Meanwhile, the Open-ended Working Group (OEWG) on ICT Security established a Global POC Directory, aiming to bolster international response to cyber incidents. Read more below.

Suspicions arose over a massive cyberattack on the UK’s Ministry of Defence, with China being implicated. The Qilin group claimed responsibility for a cyberattack on Synnovis labs, disrupting key services at London hospitals. A data breach claimed by IntelBroker targeted Europol, amplifying concerns over law enforcement data security. Additionally, Ticketmaster suffered a data breach which compromised 560 million users’ personal data, and is facing a class action lawsuit.

Infrastructure

US officials warned telecom companies that a state-controlled Chinese company that repairs international undersea cables might be tampering with them. Google announced it will build Umoja, the first undersea cable connecting Africa and Australia. Zimbabwe has granted Elon Musk’s Starlink a license to operate in the country.

Legal

In a major legal battle, TikTok and creators on TikTok have sued the US government over a law that requires the app to sever ties with its Chinese parent company, ByteDance, or face a ban in the USA. This prompted a US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia to expedite the review of the TikTok ban law.

A legal battle between Elon Musk’s X and the Australian cyber safety regulator over the removal of 65 posts showing a video of an Assyrian Christian bishop being stabbed has come to an end. In April, the Federal Court of Australia, acting upon the eSafety Commissioner’s application, issued a temporary worldwide order mandating X to hide the video content. However, in May, the court rejected the regulator’s motion to extend this order, leading the regulator to drop its legal proceedings against X.

The EU launched an investigation into Facebook and Instagram over concerns about child safety. Meanwhile, Italy’s regulatory body fined Meta for misuse of user data.

Internet economy

Microsoft, OpenAI, and Nvidia found themselves under the antitrust microscope in the USA for their perceived dominance in the AI industry. Rwanda announced plans for a digital currency by 2026, while the Philippines approved a stablecoin pilot program.

Digital rights

The European Court of Human Rights ruled that Poland’s surveillance law violates the right to privacy, lacking safeguards and effective review. Bermuda halted its facial recognition technology plans due to privacy concerns and project delays, reflecting global hesitations about the technology’s impact on civil liberties.

OpenAI was criticised for using Scarlett Johansson’s voice likeness in ChatGPT without her consent, highlighting issues of privacy and intellectual property rights. GLAAD’s report found major social media platforms fail to handle the safety, privacy, and expression of the LGBTQ community online.

Google launched its Results about you tool in Australia to help users remove search results that contain their personal information. Leading global internet companies are working closely with EU regulators to ensure their AI products comply with the bloc’s data protection laws, Ireland’s Data Protection Commission stated. However, OpenAI is in hot water with the European Data Protection Board over the accuracy of ChatGPT output.

Development

The EU has officially enacted the Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA) to bolster clean technologies manufacturing within the EU.

South Africa pledged to bridge the digital divide in the country and expand internet access for all. Morocco launched a programme to expand high-speed internet to 1,800 rural areas. The Connected Generation (GenSi) programme was launched to provide digital skills to youth and women in rural Indonesia.

Sociocultural

The EU launched an investigation into disinformation on X after the Slovakian Prime Minister’s shooting. X also officially began allowing adult content.

Morroco announced its Digital Strategy 2030, which aims to digitise public services and enhance the digital economy to foster local digital solutions, create jobs, and add value. Zambia reached a key milestone in digital ID transformation, digitising 81% of its paper ID cards in 3 months.

OpenAI announced that it had disrupted five covert influence operations that misused its AI models for deceptive activities online, targeting issues such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Gaza conflict, Indian elections, and politics in Europe and the USA. A survey revealed widespread concerns about potential AI abuse in the upcoming US presidential election. EU elections are a hot topic at the beginning of June. The EU accused Russia of spreading disinformation ahead of these elections, and a study found TikTok failed to address disinformation effectively before the elections. Interestingly, Microsoft reported that AI had minimal impact on disinformation surrounding the elections.

New York lawmakers are preparing to ban social media companies from using algorithms to control content seen by youth without parental consent. Meanwhile, Australia announced a trial for age verification technologies to improve online safety for minors.

Digital governance in focus at WSIS+20 Summit and AI for Good Global Summit 2024

The last week of May saw two attention-grabbing digital events: the WSIS+20 Forum and the AI for Good Global Summit. The former was featured heavily on the agenda of digital policymakers, given the upcoming 20-year review of the implementation progress of the WSIS outcomes as defined in the Geneva Declaration and the Tunis Agenda. Meanwhile, 2024 also saw the negotiation of the Global Digital Compact (GDC), where UN member states are to reaffirm and strengthen their commitment to digital development and effective governance. It is only natural that during this year’s WSIS+20 Forum, a question lingered on the tip of everyone’s tongue: What is the relevance of the WSIS outcomes in light of the GDC?

According to the first revision of the GDC, UN member states are to ‘remain committed to the outcomes of the [WSIS]’. Stakeholders gathered at the WSIS+20 Forum to reflect on and compare the GDC and the WSIS+20 review processes. Among participants, there was an evident concern about duplicating existing frameworks for digital governance, which increases the complexity and burden for stakeholders to follow and implement both processes; speakers emphasised the need to align the two processes, and especially to leverage the inclusive multistakeholder model laid out by the WSIS process. Some reiterated the importance of the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), a key digital policy platform for multistakeholder discussion born from the Tunis Agenda, to be harnessed in the implementation and alignment of both the WSIS Action Lines (ALs) and the GDC principles. Some stressed the necessity of concrete follow-up mechanisms to the GDC and suggested that the WSIS+20 review process be a critical time of reflection. Still others looked at the regional dimension, underscoring local needs, multiculturalism, and multilingualism as essential to be reflected in both processes.

There was also a more nuanced discussion around the relevancy of the overall WSIS process to digital governance. Ahead of the 20-year review in 2025, experts reflected on the achievements of the WSIS process so far, especially in fostering digital cooperation among civil society groups, the private sector, and other stakeholders. Some called for increased collaboration among the UN system to make more substantive progress in the implementation of the WSIS ALs; others encouraged the technical community to be further integrated into the WSIS+20 review process.

The AI for Good Global Summit, on the other hand, is relevant to digital governance in two ways. For one, it serves as a platform for AI actors to convene, exchange, network, and seek scaling opportunities. Not only does the ITU initiative feature a global summit, but it also hosts year-round workshops and initiatives that encourage AI developers and researchers to innovate creative solutions to global challenges. In the first revision of the GDC, AI for Good is also mentioned for its role as a mechanism for AI capacity building.

Second, the AI for Good Global Summit provides a platform for business leaders, policymakers, AI researchers, and others to openly discuss AI governance issues, exchange high-potential use cases in advancing the SDGs, and establish cross-sectoral partnerships that go beyond the 3-day event. This year’s summit featured an AI governance day where high-level policymakers and top AI developers can deliberate on major AI governance processes, the role of the UN system in advancing such processes, and the conundrum for governments to balance risks and gains from AI development.

The conversations at the summit featured more technical topics than conventional policy discussions. Experts evaluated the pros and cons of open source vs proprietary large language models (LLMs) and the potential to set standards for the harmonisation of high-tech industries or responsible and equitable development of the technology. Linguistic and cultural diversity in AI development was also highlighted as key, especially as LLMs are taking centre stage.

GIP provided just-in-time reports from WSIS+20 and AI for Good Global Summit.

The WSIS+20 Forum High-Level Event, part of the World Summit on the Information Society process, was held 27–31 May. The meetings reviewed progress related to information and knowledge societies, shared best practices, and built partnerships.

The AI for Good Global Summit was held 30–31 May, in Geneva, Switzerland. This event, part of the AI for Good platform, focused on identifying practical AI applications to advance the SDGs globally.

Do we need a digital social contract?

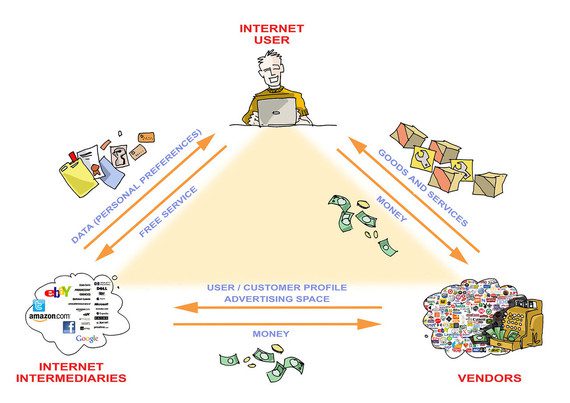

You might be familiar with the concept of social contract. The idea is that individuals want to leave behind the state of nature, where there is no political order, and they form a society, consenting to be governed by an authority in exchange for security or civil rights.

The digital age raises the question: Can the state deliver on its part of the social contract? Do we need a new social contract for the online era, which will re-establish the relationship of trust between citizens and the state? Is it enough to bring citizens and the state to the same table? Or should today’s social contract also specifically involve the technical community and the private sector, which manage most of the online world?

Modern society may need a new social contract between users, internet companies, and governments, in the tradition of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan (exchange freedom for security) or Rousseau’s more enabling Social Contract (individual vs commercial/political will). The new agreement between citizens, governments, and businesses should address the following questions: What should the respective roles of governments and the private sector be in protecting our interests and digital assets? Would a carefully designed checks-and-balances system with more transparency be sufficient? Should the new social contract be global, or would regional and national contracts work?

A social contract could address the principal issues and lay the foundation for the development of a more trustworthy internet. Is this a feasible solution? Well, there is reason for cautious optimism based on shared interests in preserving the internet. For internet companies, the more trusting users they have, the more profit they can make. For many governments, the internet is a facilitator of social and economic growth. Even governments who see the internet as a subversive tool have to think twice before they interrupt or prohibit any of its services. Our daily routines and personal lives are so intertwined with the internet that any disruption to it could catalyse a disruption for our broader society. Thus, a trustworthy internet is in the interests of the majority.

Rationally speaking, there is a possibility of reaching a compromise around a new social contract for a trusted internet. We should be cautiously optimistic, since politics (especially global politics), like trust (and global trust), are not necessarily rational.

This text was adapted from the opinion pieces ‘The Internet and trust’ and ‘In the Internet we trust: Is there a need for an Internet social contract?‘

The blog explores the critical role trust plays in the fabric of internet governance and digital ecosystems. It argues for strengthened trust mechanisms to enhance security and cooperation in the digital age.

The author examines the necessity of an internet social contract to foster trust and cooperation online, highlighting the importance of defining digital rights and responsibilities for a harmonious cyberspace. This contemplation stresses the need for a collective agreement to guide internet behaviour and governance.

AI governance milestones in Europe

In the span of a week, two significant developments in AI governance happened in Europe: the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers adopted a convention on AI and human rights, while the European Council gave final approval to the EU AI Act. Reads just a bit confusing at first glance, doesn’t it?

Firstly, these are different bodies: The Council of Europe (CoE)is a European human rights organisation, while the European Council is one of the executive bodies of the EU. Secondly, logically, the two documents in question are also different, yet they share many similarities.

Both documents define an AI system as a machine-based system that infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments.

Both documents aim to ensure AI systems support and do not undermine human rights, democracy, and the rule of law. However, the CoE’s framework convention provides a broad, overarching structure applicable to all stages of the AI lifecycle. The EU’s AI Act is more specific to the EU’s single market and also aims to ensure a high level of protection of health, safety, and environmental protection.

A risk-based approach is adopted in both documents, meaning the higher the potential harm to society, the stricter the regulations are. Both documents highlight that natural persons should be notified if they are interacting with an AI system, and not another natural person.

Neither of the documents extends to national security and defence activities. Neither document covers AI systems or models developed for scientific research and development.

Parties to the CoE convention can assess whether a moratorium, a ban or other appropriate measures are needed with respect to certain uses of AI systems if the party considers such uses incompatible with the respect for human rights, the functioning of democracy or the rule of law.

The CoE convention is international in nature, and it is open for signature by the member states of the CoE, the non-member states that have participated in its drafting, and the EU. It will be legally binding for signatory states. The EU AI Act is, on the other hand, applicable only in EU member states.

Further, the measures enumerated in these two documents are applied differently. In the case of the CoE framework convention, each party to the convention shall adopt or maintain appropriate legislative, administrative or other measures to give effect to the provisions set out in this convention. Its scope is layered: While signatories are to apply the convention to ‘activities undertaken within the lifecycle or AI systems undertaken by public authorities or private actors acting on their behalf’, they may decide whether to apply it to the activities of private actors as well, or to take other measures to meet the convention’s standards in the case of such actors.

On the other hand, the EU AI Act is directly applicable in the EU member states. It does not offer options: AI providers who place AI systems or general-purpose AI models on the EU market must comply with the provisions, and so must providers and deployers of AI systems whose outputs are used within the EU.

Our conclusion? The CoE convention has a broader perspective, and it is less detailed than the EU Act, both in provisions and in enforcement matters. While there is some overlap between them, these two documents are distinct yet complementary. Parties that are EU member states must apply EU rules when dealing with each other on matters covered by the CoE convention. However, they must still respect the CoE’s convention’s goals and fully apply the convention when interacting with non-EU parties.

The red telephone of cyber: The POC Directory

The concept of hotlines between states, serving as direct communication lines for urgent and secure communication during crises or emergencies, was established many years ago. Perhaps the most famous example is the 1963 Washington-Moscow Red Phone, created during the Cuban Missile Crisis as a confidence-building measure (CBM) to prevent nuclear war.

In today’s cyberworld, where uncertainty and interconnectedness between states are increasingly higher, and conflicts are not unheard of, direct communication channels are indispensable for maintaining stability and peace. In 2013, states discussed points of contact (POCs) for crisis management in contexts of ICT security for the first time.

After a decade of discussions under the auspices of the UN, states finally agreed on elements for the operationalisation of a global, intergovernmental POC directory as a part of the UN Open-ended working group (OEWG) Annual Progress Report (APR).

What is the POC directory and why is it important? The POC directory is an online repository of POCs which aims to facilitate interaction and cooperation between states to promote an open, secure, stable, accessible, and peaceful ICT environment. The directory is intended to be voluntary, practical, and neutral, aiming to increase information sharing between states and further the prevention, detection, and response to urgent or significant ICT incidents through related capacity-building efforts.

In January 2024 the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) invited all states to nominate, where possible, both diplomatic and technical POCs. In May 2024, UNODA announced that 92 states have already done so. UNODA also announced the launch of the global POC Directory and its online portal, marking the operationalisation of these CBMs in the sphere of ICT security.

The first ping test is planned for 10 June 2024, and further such tests will be conducted every six months to keep the information up-to-date. The work on the directory will complement the work of the Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs) and Computer Security Incident Response Teams (CSIRTs) networks.

Each state decides how to respond to communications received via the directory. Initial acknowledgement of receipt does not imply agreement with the information shared, and all information exchanged between POCs is to remain confidential.

Before the establishment of the global POC directory at the UN level, some states already used POCs at bilateral or regional levels, such as the ASEAN-Japan cybersecurity POCs, OSCE network of policy and technical POCs, CoE POCs established by the Budapest Convention, and INTERPOL POCs for cybercrime. While these channels may overlap, not all states are members of such regional or sub-regional organisations, making the global directory a crucial addition.

Capacity-building efforts also accompany the directory, and this is probably one of the most important elements in the directory. For example, the OEWG chair is tasked with convening simulation exercises to use basic scenarios to allow representatives from states to simulate the practical aspects

of participating in a POC directory and better understand the roles of diplomatic and technical POCs. Additionally, regular in-person and virtual meetings of POCs will be convened. A dedicated meeting will be held this year to implement the directory and consider necessary improvements, so we should expect further updates on the directory’s practical implementation.

Reducing terminological confusion: Is it digital or internet or AI governance?

Digital and internet are used almost interchangeably in governance discussions. While most uses are casual, the choice sometimes signals different governance approaches.

The term digital is about using a binary representation – via ‘0’ and ‘1’ – of artefacts in our social reality. The term internet refers to any digital communication that is conducted via the Transport Communication Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP). You’re probably reading this text thanks to TCP/IP, which carries digital signals (0s and 1s) that represent letters, words, and sentences. Using both terms correctly describes what is going on online, to introduce a third term, and in digitised information.

Should we use the term internet governance in a more specific sense than digital governance? The answer is both yes and no.

YES, one could say that all digital phenomena with relevance for governance are communicated via TCP/IP, from content to e-commerce and cybercrime. Most AI aspects that require governance are about using the internet to interact with ChatGPT or to generate images and videos on AI platforms.

For instance, regulation of deep-fakes generated by AI is and internet governance issue, as harm to society is caused by their distribution through the internet and social media powered by TCP/IP, the internet protocol. If we have deepfakes stored on our computers, it does not require any governance as it does not cause any harm to society.

The answer NO relates to the increasing push to govern AI beyond its uses through the regulation of algorithms and hardware on which AI operates. This approach to regulating how AI works under the pretext of mainly long-term risks is problematic, as it opens the door to deeper intrusion into innovation, misuses, and risks that can affect the fabric of human society.

As proposals for AI governance become more popular, we should keep in mind two lessons from tech history and internet governance.

First, the internet has grown over the last few decades precisely because it has been regulated at the uses (applications) level. Second, whenever exceptional management went deeper under the bonnet of technology, it was done with full openness and transparency, as has been the case with setting TCP/IP, HTML, and other internet standards.

In sum, if AI governance takes place at the uses level, as has been done for most technologies in history, it is not different from internet governance. Although it may sound heretical, given the current AI hype, one might even question whether we need AI governance at all. Perhaps AI should be governed by existing rules on intellectual property, content, commerce, etc.

Stepping back from the whirlpool of digital debates could help us revisit terminology and concepts that we might have taken for granted. Such reflections, including how we use the terms internet and digital, should increase clarity of thinking on future digital/internet/AI developments.

This text was first published on Diplo’s blogroll. Read the original version.

The blog discusses the importance of distinguishing between digital and internet governance. It emphasises the need for precision in terminology to accurately describe online activities and the governance required.