Digital business models

We engage in business relations online on a daily basis. In some of these transactions, the commercial aspect is clear, such as buying products in an e-commerce platform, renting storage space from a cloud service provider, or using a ride-hailing service as a means of transportation, such as Uber or Lyft. In these cases, a financial payment is made by the customer. In other cases, the commercial aspect is harder to identify. Several companies provide services to internet users without apparent financial compensation; such as search engines, many email providers, social media platforms, and some apps. In this business model, user data is the core economic resource, and companies generate most of their income from selling information about user preferences to advertisers.

Despite these differences, digital business models have one thing in common: they are increasingly built around the flow of data. In recent years, data has shifted from a peripheral business resource to a central one, sometimes described as the ‘oil of the digital economy’. Internet companies and other businesses are in a ‘gold rush’ for data, which will determine their competitiveness and market survival.

The evolution of digital business models raises many challenging issues. How to ensure consumer protection when transactions occur across multiple jurisdictions? How to regulate companies that are part of the flourishing ‘gig economy’ – platforms like Uber and Airbnb, which challenge incumbent operators, such as taxi drivers and hotel owners? What are the impacts of internet companies and platforms on competition and on the potential growth of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), especially in the developing world? How to distribute the economic benefits generated by the digital economy more evenly? These are some of the questions that individuals, businesses, and policymakers are confronted with.

Examples of digital business models

There are a myriad of business models based on digital technologies, from the provision of Internet access and the commercialisation of software to Internet platforms. This section will focus on three of them: cloud service provision, the Internet data model, and the platform model.

Cloud services

Cloud computing can be understood as a new way of providing IT functions such as information storage, computer processing power, and computer programmes as services over the internet. This means that as opposed to storing information and programmes on a home or company computer terminal, they are stored on external servers which are accessed via the internet, reducing costs of hardware and software.

Cloud services have become key in a globalised world, in which outsourcing and cross-disciplinary work have become paramount. They offer tools for teams to work together collaboratively, or to perform complex tasks that some companies choose to outsource, such as data analytics, identification of trends, data mining, calculations and other activities that require a lot of computing power.

As cloud computing becomes an increasingly dominant means of providing computing resources, the legal and policy issues associated with data in the cloud become more pronounced. These issues can be related to a wide range of areas; contract compliance, law enforcement, data protection, and the protection of particularly sensitive information such as health, finance, and intellectual property.

Moreover, since the flows of data take place irrespective of national boundaries, cloud computing also may pose jurisdiction issues and conflicts in national laws. For example, content that is considered infringing by national regulation in one country, could be lawfully hosted on servers located in another country.

Read more about Cloud computing.

Internet data

Internet companies make intensive use of data to enhance users’ experiences with customised services and also to enable other companies to more efficiently market products to selected audiences. Data is essential for the successful growth of internet companies such as Google and Facebook, which rely heavily on data-driven advertising for revenue.

In this business model, user data is the core economic resource. When searching for information and interacting on the internet, users give away significant amounts of data, including personal data generated, i.e., their electronic footprint. Internet companies collect and analyse this data to extract information about user preferences, behaviour, and habits. They also mine data to extract information about a group; for instance, the behaviour of teenagers in a particular city or region. Internet companies can predict with high certainty what a person with a certain profile is going to buy or do. In other instances, user data helps improve the product itself, particularly in artificial intelligence (AI) applications such as computer vision and speech recognition.

Internet platforms

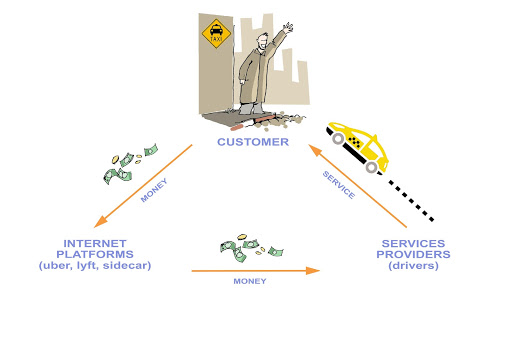

In an economic sense, a platform is the entity that allows or facilitates interaction between two sides in a market. Internet platforms facilitate economically driven interaction by using digital infrastructure and generate revenue from their intermediary roles. Internet platforms are the digital successor to pre-digital platforms, such as village markets or shopping malls.

Typically, the internet platform model is based on the utilisation of resources which were not previously offered by the market. For example, Uber enabled privately-owned cars to be used similarly to taxis, and Airbnb allowed privately-owned rooms to be used analogously to hotel rooms. These types of businesses – which are known as the ‘gig economy’ or the sharing, access or collaborative economy – have three main features in common: a prevalence of contractual and temporary employment, a digital platform/app for (quasi) peer-to-peer transactions, and a rating system for evaluating the quality of the service provided.

Internet platforms are often the focus of policy controversy because they challenge incumbent operators without necessarily abiding by the same regulatory and tax norms. Courts around the world are confronted with the need to decide if they are information services or traditional services that are simply using information technology. Another policy-related issue concerns the protection of worker social well-being and labour rights in the context of the gig economy.