Taxation

Let's start: Some basic principles of digital taxation

What did the scientist Michael Faraday reply to the politician who asked him about the purpose of his newly invented electromagnetic induction? ‘Sir, I do not know what it is good for. But of one thing I am quite certain, some day you will tax it.’ Over the years, the growth of the digital economy – and how to tax it – propelled governments into asking whether existing tax rules are fit for the digital age. The creative tax practices, adopted by some of the largest tech companies, fuelled this question even further, and today, some of the global taxation rules affecting the digital economy are very close to being overhauled.

What is the difference between direct and indirect taxation?

There are two broad categories of taxation affecting the digital economy. The first is ‘corporate tax’ (or ‘company tax’), that is, the tax imposed by jurisdictions directly on companies over the income they make in that country. This is referred to as ‘direct taxation’ and is the equivalent of a person paying tax on his or her income. In recent years, US companies have been setting up their headquarters in European countries with low corporate tax rates, such as Ireland. This meant that other countries whose citizens were also customers of US companies have not been able to tax the companies since there was no physical ‘nexus’. In addition, most jurisdictions only tax their companies’ domestic income, since they assume that foreign income will be taxed in other countries. It became clear, therefore, that the old rules of linking corporate tax to a company’s physical location were no longer fit for today’s reality. The second is ‘consumption tax’, that is, a tax levied on consumers over the things or services they consume. Examples include value added tax (VAT), sales tax, and excise tax. Since the tax is levied by the companies or people we buy our goods or services from, this is referred to as ‘indirect taxation’.

Updating the corporate global tax rules

The question of how to update corporate tax rules is the most pressing issue in digital policy when it comes to taxation. One of the earliest calls for taxing the digital economy came from France in 2013. Others were quick to follow, either by calling for updated rules or by introducing unilateral tax rules for the digital economy.

The attractive world of tax avoidance

Companies’ creative exercises to avoid paying taxes – albeit through legal ways – heightened the urgency for reform. Italy claimed that Google evaded 227 million in taxes between 2009 and 2013. The £130 million tax agreement between the UK national tax authorities and Google was criticised as ‘too lenient’ on the company. In one of the landmark cases on taxation, in 2016 the European Commission ordered Apple to pay the Irish state up to 13 billion in taxes after an investigation into Apple’s ‘sweetheart tax’ granted by Ireland, which it said was unlawful state aid. In the same year, the French government even organised a search in Google’s Paris headquarters as part of an investigation into tax fraud, as France accused the company of owing it €1.6 billion in unpaid taxes. Studies repeatedly showed that tech companies were among the top multinationals involved in tax-avoidance schemes.

Reforms on tax avoidance

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has been leading global negotiations on reforming tax rules for many years. One of the first landmark results was the creation of the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes in 2009. With over 160 member jurisdictions, the Global Forum reviews and rates the countries’ compliance to high standards of transparency. This includes the ‘exchange of information on request’ (EOIR) standard. A second result, specifically targeting tax avoidance, came in 2013 with the launch of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project. Under this project, a package of 15 measures was published in October 2015, endorsed by the G20 ministers of finance, and later, the G20 leaders. In January 2016, the European Commission also presented an Anti Tax Avoidance Package, which aimed at preventing companies in the EU from shifting their profits to low-tax countries. Throughout these years, countries considered as tax havens have been gradually updating their tax frameworks to close legal loopholes. However, this still resulted in a patchwork of tax rules. More solutions were needed to address the tax challenges of the digital economy.

Reforms on a fairer distribution of profits

In November 2015, the OECD and the G20 took the BEPS project forward by agreeing to establish an ‘inclusive framework’, which kicked off in 2016. The aim was to bring countries and jurisdictions to work together on an equal footing to reform the global tax rules. As of April 2021, there were 139 members of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS, including 68 developing countries With the issue of tax avoidance being tackled by the BEPS project, countries turned their attention to the distribution of profits. At this stage, the question was not whether to tax the companies in the digital sector. Companies know – and agree – they need to pay tax. Rather, it’s a question of where should companies pay tax, and how to update the tax rules for a fairer distribution of taxes.

Taxing the consumption of goods and services

The internet governance dilemma of whether cyber issues should be treated differently from real-life issues is clearly mirrored in the question of taxation. Since the early days, the USA has been attempting to declare the internet a tax-free zone. In 1998, the US Congress adopted the Internet Tax Freedom Act (ITFA). After this act was extended several times, the US Senate finally decided to pass legislation that permanently bans states and local governments from taxing internet access. In addition to the permanent extension of the ITFA, the measure bans some taxes on digital goods and services. The OECD and the EU have promoted the opposite view, that is, that the internet should not have a special taxation treatment. The OECD’s Ottawa Principles (outlined in the Electronic Commerce: Taxation Framework Conditions report that was endorsed by the OECD Ministerial Conference in 1998) specify that taxation of e-commerce should be based on the same principles as taxation for traditional commercial activities: neutrality, efficiency, certainty and simplicity, effectiveness and fairness, and flexibility. The European Commission reiterated that ‘there should not be a special tax regime for digital companies. Rather the general rules should be applied or adapted so that “digital†companies are treated in the same way as others.’ Following the view that the internet should not have special taxation treatment, the EU introduced legislation in 2003 requesting non-EU e-commerce companies to pay VAT if they sold goods within the EU. The main motivation for the EU’s decision was that non-EU (mainly US) companies had an edge over European companies, which had to pay VAT on all transactions, including electronic ones. Meanwhile, the OECD also developed standards and mechanisms to ensure that sellers collect VAT in their customers’ countries, and forward it where it is due. They were included in the 2015 BEPS Action 1 Report, and in implementation guidelines issued by the OECD since then.

The OECD two-pillar global corporate tax rules

What were the main issues, and why were these new rules needed urgently?

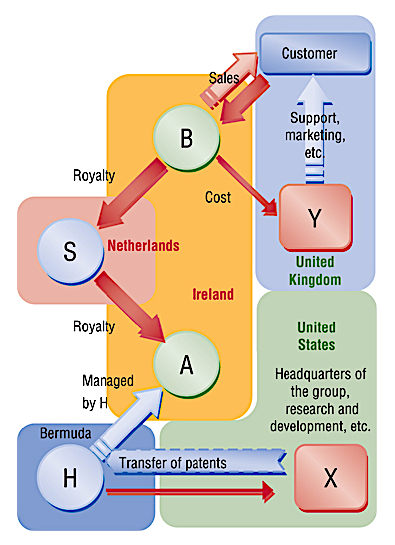

First, existing rules are based on a very old system where tax is based in the country in which a company is headquartered. This doesn’t make much sense in the digital age where these giant companies deal with users in practically every country around the world. Tech companies will therefore fall under these rules, regardless of where they are headquartered. Second, companies have been able to employ some very creative practices – most of which were perfectly legal. A typical practice, used by a bunch of giant US tech companies, would make use of the company’s intellectual property to relocate profits to a tax haven (such as Bermuda), utilising subsidiaries in Ireland and the Netherlands as conduits. Such schemes had creative names too: from the ‘double Irish with a the Dutch sandwich’ to the ‘single malt’ avoidance strategies.

How was the OECD’s two-pillar solution born?

After several years of work, including complex technical work, in October 2020 the Inclusive Framework agreed on a new solution: ‘blueprints’ for a taxation system built on two pillars:

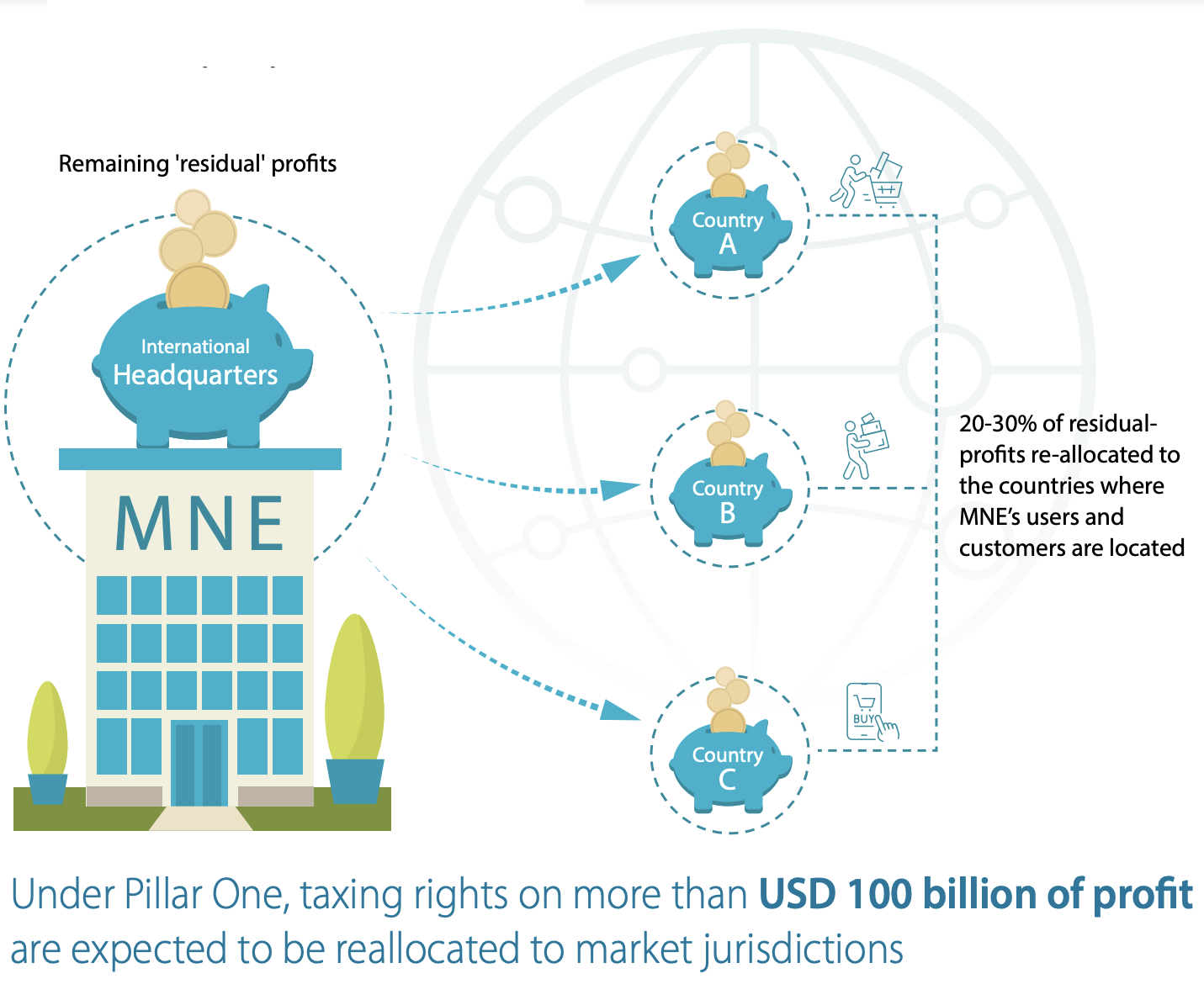

- Pillar One: Establishes new rules for the allocation of profits

- Pillar Two: Ensures that companies pay a minimum level of corporate tax on foreign income

The culmination of the OECD-led negotiations came in July 2021 when 130 countries agreed on an updated and more refined version of the rules.

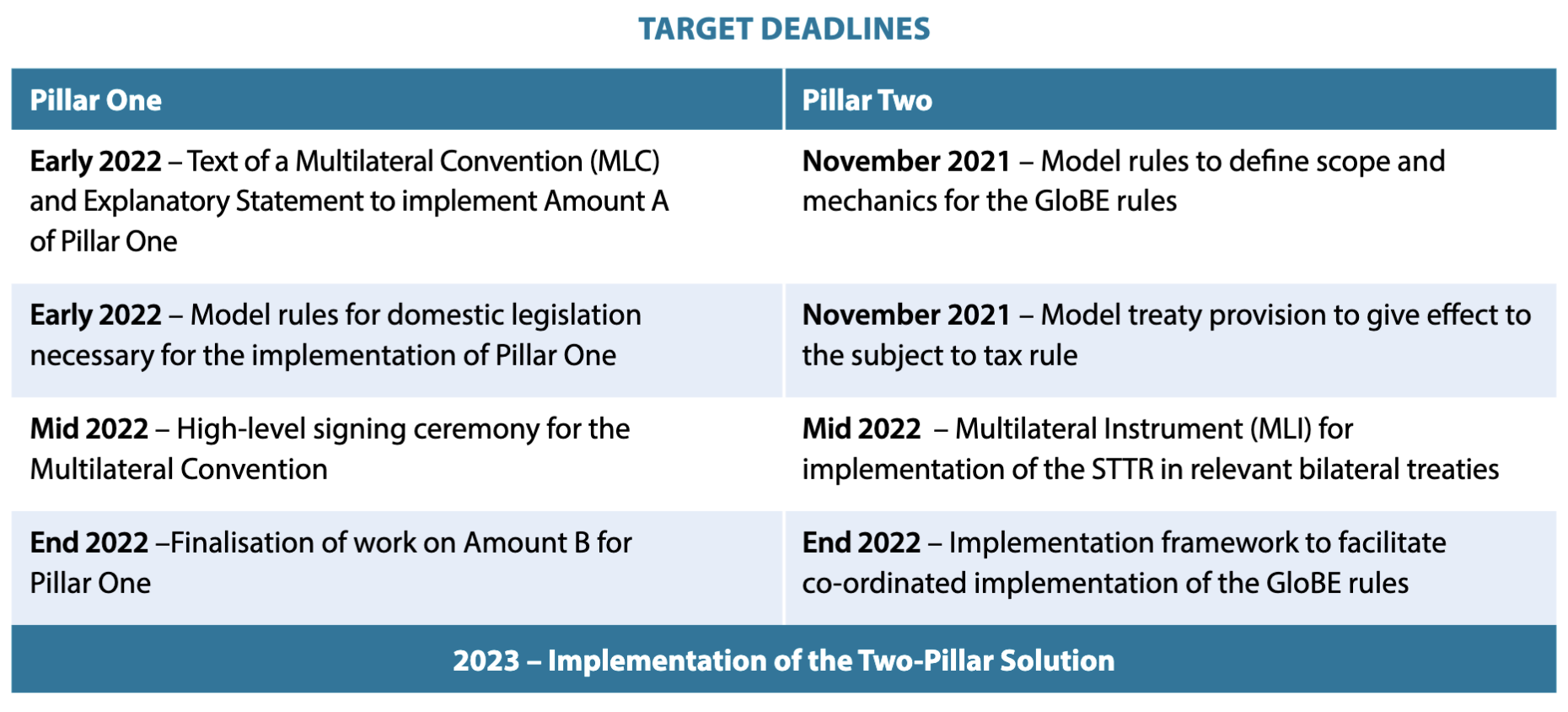

The original timeline, now grossly outdated, was the following (read more on the new timelines:

Do these rules target digital companies specifically?

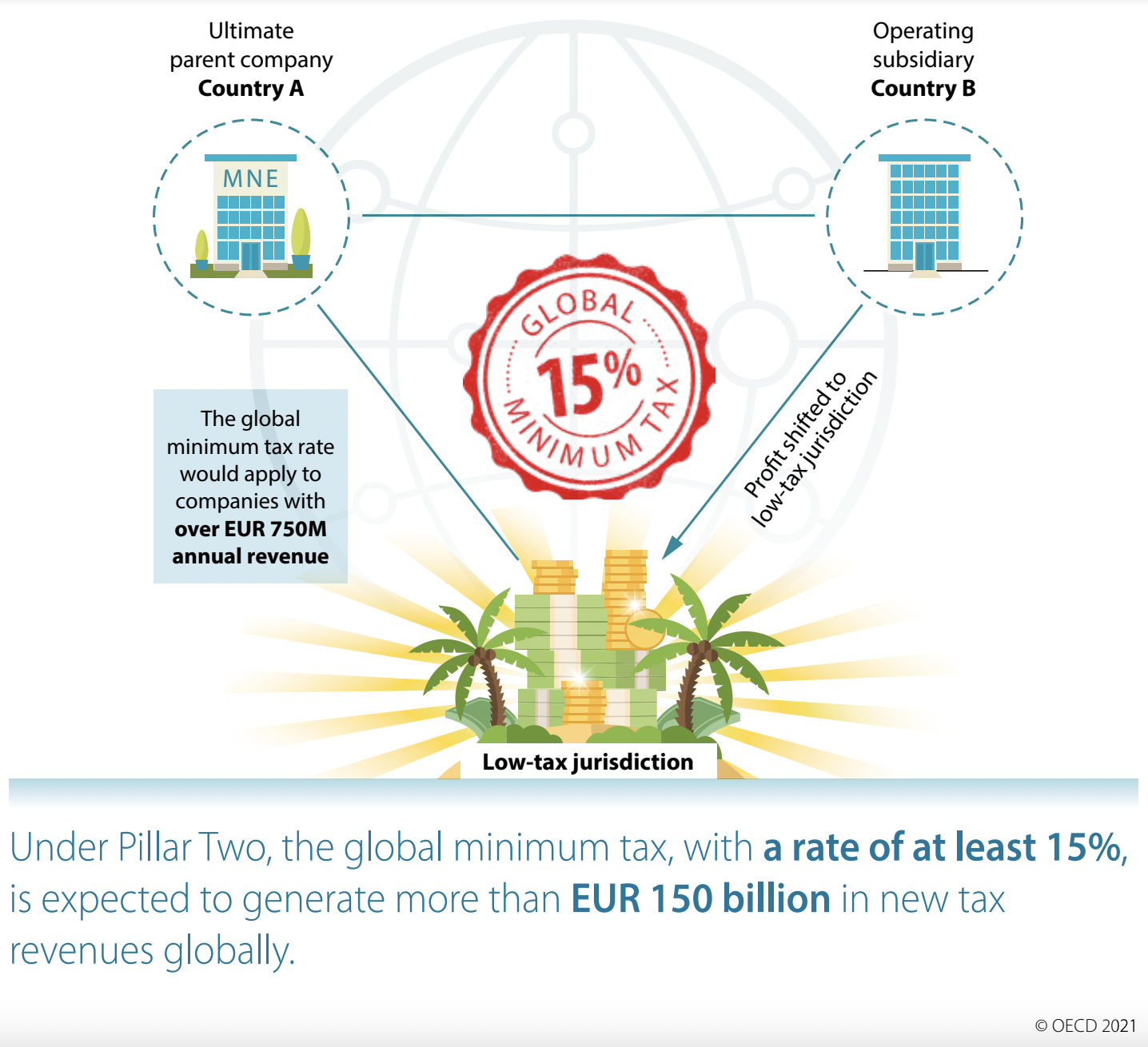

No, the new rules are not specific to digital companies, but they will certainly affect them. Pillar One targets companies which generate more than €20 billion in revenues, and that means Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, and Microsoft. Pillar Two affects companies which earn more than €750 million in revenues, and that’s a significantly larger number of companies, including digital companies.

And which ‘profits’ are we referring to?

We need to distinguish between domestic profits and foreign profits. Domestic profits are those profits made in the country of origin of a multinational country, that is, the international headquarters of a company. So if we’re referring to any of the giant tech companies, that’s the USA (California). Domestic profits are not an issue. Rather, the issue is with profits made by a company’s subsidiary, for instance, those linked to a company’s offices in Ireland. One of the main issues revolves around those profits which a company shifts to a jurisdiction in which it has little or no real economic activity, but has a low- or zero-tax policy. By shifting these residual profits to ‘shell companies’, a company is able to get away with paying little or no tax at all. Another issue is ‘forum shopping’ in which a company identifies low-tax jurisdiction to set up shop over there. In both cases, although the practices are not illegal, they are unfair towards those countries in which there is real economic activity, and unfair to competition in general.

So how will the new tax rules address these profit shifting schemes?

The rules under Pillar One will ensure that profits are distributed more fairly. Those very large companies, which generate more than 20 billion in revenues, will have to pay taxes on 25% of the profit they make above a 10% threshold of revenue (this is called Amount A), and will need to pay it in those countries where they are the most economically active. Countries will therefore have the right to pocket some of the taxes (on Amount A) based on a complex formula for claiming it, and tied to economic activity and the country’s own GDP (the new special purpose nexus rule). The rules under Pillar Two will ensure a healthier tax competition among countries. It will do this by imposing an obligation on every country (or almost every country) to tax companies at a minimum rate of 15% tax.

Aren’t countries supposed to have sovereign rights over their tax policy?

Yes they are, and the new rules will not change that. Countries can set any tax rate they wish, but cannot go lower than the 15% minimum rate. As the OECD describes it: ‘The global minimum tax agreement does not seek to eliminate tax competition, but puts multilaterally agreed limitations on it’.

And what will happen to all those unilateral taxes which countries introduced in the past few years?

All unilateral taxes, including digital services Taxes (DSTs), will need to be removed. The way existing taxes will be removed still needs to be ironed out. Countries will also not be able to introduce new unilateral taxes on companies. This applies immediately and is a half-win for Washington which was requesting that domestic taxes be scrapped immediately.

What was significant about the 1 July agreement?

This is when the OECD announced that 130 countries agreed to support a new two-pillar global tax solution, called the Statement on a Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising From the Digitalisation of the Economy.

And what’s significant about the 8 October agreement?

The October agreement – the so-called Statement on the Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy with a Detailed Implementation Plan – updated and finalised the July agreement. There were three important developments. First, the rate of the minimum tax under Pillar Two is now set at 15%, which is a significant change from the July agreement to tax companies at a rate of ‘at least 15%’. This was a negotiating win for Ireland. There were also other new thresholds and technical details which countries agreed upon. Second, there is now a detailed implementation plan in place. For instance, it calls for a global treaty (called the Multilateral Convention (MLC)) to be ready for signing by mid-2022. Third, new countries have agreed to sign up to the new tax rules. These include Ireland, the country which opposed the new rules the most, plus Estonia and Hungary. For the EU, having these countries on board was a significant achievement for the OECD rules.

Which countries agreed to the new rules, and who’s missing?

In July, 131 countries – out of an even larger group of 139 countries, called the OECD Inclusive Framework – signed up to the new tax rules. These included all G20 countries. The missing eight countries were: Ireland, Estonia, Hungary, Barbados, Kenya, Nigeria, St Vincent and the Grenadines, and Sri Lanka. Three of these countries are EU member states (a fourth EU country – Cyprus – was not among the original group of 139). Ireland was the country who was the most opposed to the rules. Over the years, its low-tax approach attracted lots of companies. Finally, a day prior to the OECD’s 8 October 2021 meeting, the Irish parliament agreed to join the tax deal. Read: Why the change of heart, and what’s in it for Ireland?

- See also: Africa and the new OECD taxation rules

Why does the EU have so much at stake?

One of the EU’s main aims is to have a stronger single market. Such a market cannot really evolve if companies have to deal with 27 different tax frameworks. Plus, the EU was also unhappy about the creative tax-avoidance strategies employed through some of its member countries. The downside for EU countries is that they will be relinquishing their right to impose unilateral taxes.

What about the USA, which is home to most of the world’s giant tech companies?

For the USA, the new tax rules are the culmination of a different ball game. At the end of this process, the USA will have succeeded in establishing rules for large companies across every sector, rather than affecting only the giant companies in the tech industry, most of which are American. Plus, only a small number of US multinational companies will be affected.

The global digital tax deal in 2023: What's next?

On 8 October 2021, close to 140 countries have agreed on a major global tax reform and on a detailed implementation plan. Celebrated as one of the major deals brokered by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the global tax deal faces a tough test: how to implement it.

The negotiations on Pillar II are the most advanced. Countries around the world have been publishing draft proposals and launching national public consultations. In December 2022, the EU finally agreed on a draft directive to implement Pillar II in the EU bloc. This came after almost a year of negotiations, first blocked by Poland, and then blocked by Hungary for six months. The USA has also passed a 15% minimum tax (the Inflation Reduction Act), however it still needs to be refined (or reconciled) with the OECD’s global minimum tax to be fully compliant with Pillar II. So what to expect in 2023?

These negotiations will continue. The USA has work to do. So does the EU, albeit the major impasse seems to be over now. The ultimate aim is that all countries who agreed to the OECD global tax deal in 2021 will eventually have their legislation in order. With the exception of the handful of countries in the no-camp, corporations will not be able to seek refuge in any tax havens, as most countries will have a minimum of 15% tax rate.

However, since the pillars are tied together, we can also expect that some countries will not want to go all the way on Pillar II before there is enough groundwork on how to implement Pillar I.

The negotiations on Pillar I are also moving forward. One of the main challenges is that the technical discussions are complex – and lengthy. Pillar I will also require countries to drop their unilateral taxes. But if the process takes too long, especially on the USA side (USA companies will be hit the most by the new global tax rule), countries such as Canada will continue threatening to impose new unilateral taxes, or keep existing ones in place. So what can we expect here?

In 2023, complex negotiations will continue designing Pillar I’s ‘Amount A’ (the new taxing right for jurisdictions over parts of the profits made by multinational companies) and ‘Amount B’ (how to price a company’s baseline marketing and distribution activities). The multilateral convention originally planned to be finalised by mid-2022, is now expected by mid-2023. When it comes to the more advanced Pillar II, the multilateral instrument that will implement parts of the new rules is now also expected to be finalised by mid-2023.

Meanwhile, the biggest risk is stalled negotiations related to Pillar I, which could jeopardise the implementation of Pillar II. Countries could also continue to propose new unilateral tax rules in the hope that this will speed up Pillar I negotiations. Whatever unilateral rules are proposed, these will have to be temporary until the global OECD rules are implemented.

There is also an ongoing debate on the impact on developing countries: All of these rules, developing countries say, will favour mostly developed countries, so, there needs to be more incentive for developing countries to implement them. In addition, the rules are too complex. What can we expect here? Major players in the global tax deal debate are the USA and the EU. Developing countries may continue to raise concerns, but they do not have enough leverage to change the rules. Regarding complexity, we can also expect the OECD to try to simplify the implementation of the rules, as it started doing in 2022. It’s a tall order, however – tax rules are inherently complex.